What can you learn from a landscape photographer?

A lot.

I've told the story about the first time I went out shooting with Galen Rowell. It's well worth reading because some of the things that came out of that experience are going to show up in today's lesson.

Previous to taking some extension classes at UC Santa Cruz and UC Berkeley in the 1980’s, I really hadn't had any formal landscape training. To me, landscape photography was basically "go somewhere with an interesting well-known feature and take a picture of it." Thus, you go to Yosemite to take a picture of Half Dome, to Yellowstone to take a picture of Old Faithful, to Mt. Rainier to take a picture of Mt. Rainier ;~), and so on. There's 59 big National Parks in the US, and some have multiple interesting features, so maybe there's a couple of hundred of shots to go get.

Nope. That's collecting, not photography (see this article).

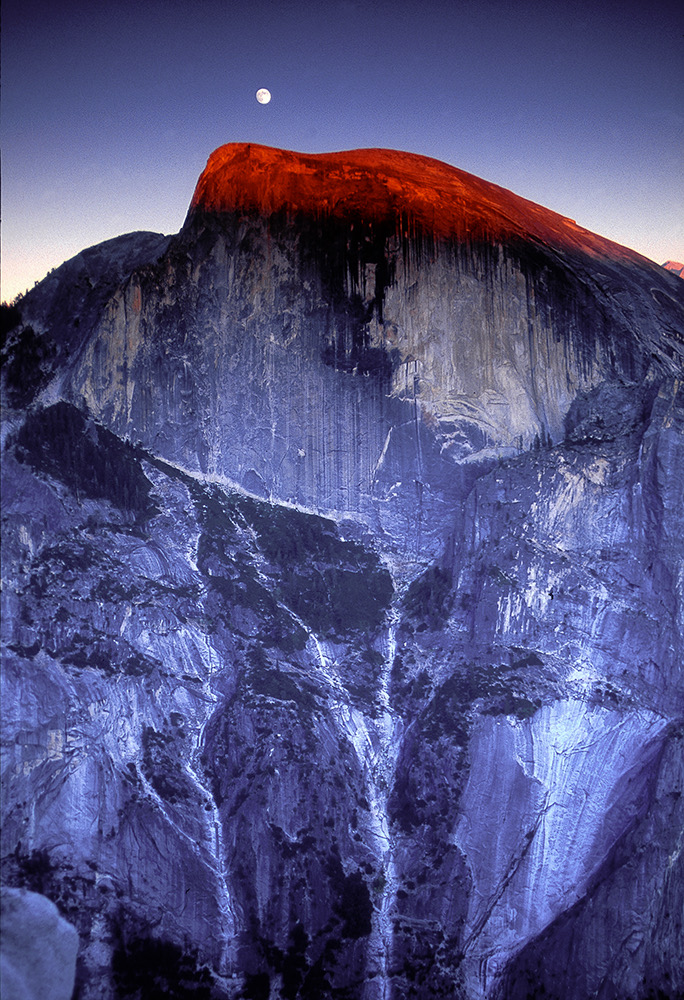

Where the heck is this? And why is it so blue and dim? Can't be in a National Park, can it? (Yes, it is.)

As it turns out, my first formal landscape photography class was at Pt. Reyes National Seashore. Despite being a Bay Area resident most of my life up to that point, I hadn't actually been to Pt. Reyes nor had I paid it a lot of attention ("it's only a National Seashore, not a National Park"). So I didn't exactly have a notion of what well-known feature I needed to go to, let alone how to photograph it. That was a good thing, actually. Especially since our instructor didn't take us to any of those places first. Instead, we spent all morning and most of an afternoon in a small meadow next to a wooded area. Say what? You want me to take pictures of plants?

But there was a method to his madness: it forced us to look. In fact, I spent a lot of time looking before I even fired off one shot. Of course, this was in the film days, so every shot was going to cost me money, too, which does really slow you down and allow you to look around.

And sure enough, the more I looked around, the more I saw. There were interesting things everywhere if I just took the time to look. Eventually I started doing some shooting and the day ended up passing quickly. I sometimes go back and look at those shots. Not because they're great photos, but because I can see the freshness and naiveté in them. I was like a baby seeing something for the first time, and trying to respond to it.

The great landscape shots have that in them: they make you relate to the place in some way. They evoke something. There's emotion in them. They don't just show a thing, they make you feel the thing.

So how is it that the landscape photographer does this? Once again there are questions you should be asking as you take photos. Let's try a few of them out and see where they take us:

1. What do I feel? Can I capture it?

2. Where's the spot? Why is that the spot?

3. Where's the point of focus, what's the depth of focus?

4. Can I capture a true feeling of depth of the landscape?

5. When should I come again? Is there a better time to take this photo?

That first question is the most important. If you're not feeling anything, why are you photographing? If you are feeling something, why doesn't your photo show it? The very best landscape photographers are asking themselves those questions all the time. I've been with a number of them out on shoots, and when you poke and prod them about what they're doing, in virtually every case you get some variant that uses the word "capture." They're trying to capture a feeling, a response, an element they've discovered, something they sense.

Most of us use the word "capture" much more mechanically, as in "I pressed the button after setting all the dials to the right values." Yeah, technique is important, but only in support of something else: the sense of place.

Yep, another famous National Park. This image has absolutely nothing you'd normally associate that park with in it. But it sure captures the feeling of coming, isolated storm.

Take out some of your landscape shots (and those of others) and evaluate them on this criteria: does it give you a sense of place? Can you imagine yourself there? Can you feel something from the photo that you'd feel at that place if you were standing there? What sounds, smells, and tastes does the photo convey? Is something in the scene big or small have a relationship with something else? Are you overwhelmed with something?

Adjectives and verbs and adverbs are the province of the great landscape photographers, not nouns. That’s a really good thing to learn. It applies to other types of photography just as well. Ever seen a sports photograph that made you feel something? Yeah, that bone-crushing blow was really good at evoking an emotion, wasn’t it?

Great landscape photographers are also not static. They don't settle for side-of-the-road, they don't settle for first-place-I-saw-it, they don't accept their first impression of where to take a shot without challenging that. Landscape photographers move around a lot. They look at a waterfall from the top, the sides, the bottom, behind it, in front of it, basically anywhere they can put their body.

Jack Dykinga, one of the best landscape photographers I know, once showed all that in an article for Popular Photography (March 2003). We saw the shot he first attempted at a waterfall, then subsequent explorations, each of which is considerably different than the original. He’s sold all six of the shots he showed in that article to other publications at some point, so it’s not exactly as if one is “better” than the other. But note that he was using Point #2: where is the spot and why? Each shot was pretty much from a different position relative to the waterfall.

To some degree, Dykinga’s article also addressed #3, but I have a better example of that: Half Dome. We all know Ansel Adams’ Moon and Halfdome shot. But even from that same position on North Dome you can get other shots, such as this one.

Quite different than Ansel's version, isn't it? I call this Half Dome Dominates the Moon.

In Ansel’s shot, the point of focus is more balanced between the moon and Half Dome. In my shot, Half Dome dominates. More across the valley to Glacier Point and you get a totally different set of things you can focus on, including the reason why the rock is called Half Dome. The great landscape photographers look for those differences and exploit them.

I’ve written about depth before and probably need to do more, as it’s one of the most important things you can learn from a landscape photographer. When a landscape photographer busts out the really wide lens, it isn’t usually because they’re trying to cover a wide vista, it’s because they want to push more depth into their photograph: the thing that’s close in their shot (bush, flower, animal, rock, etc.) requires the wide angle to get it in the frame because of how close they get to it. The far in the shot is probably the thing you thought they wanted the lens for, but note how small a portion of the frame the far tends to be in those shots! The photographer is using size to convey depth (big is near, small is farther away).

But if you really want to learn how to show depth, look really closely at how the great shots with a near/far depth relationship work through the middle. To really get the feeling of depth, you need a strong near, a strong middle, and a strong far. Depth is a continuous thing. If all you have is a near/far with no middle, you actually have a relationship shot (near thing versus far thing, how do they relate?). But if you capture near, middle, far successfully, you have a depth shot.

Finally, there’s something that a lot of landscape photographers don’t talk about, but you need to know: how many times did they go to that place before they got the exact shot they wanted? The answer is usually not "once”. It’s often dozens of times.

Why is that? Because there are a ton of factors that go into making a successful shot. Light is one of them, and it varies at different times of year in most places. It varies at different times of day. Skies vary hour by hour, day by day, season by season. So does plant and animal life. Sometimes its about the number of other visitors who are at that place and might be in the shot. Or getting the same shot.

To make your landscape shot stand out from the others, you have to get everything right, and that means being there with the right gear at the right time. Today might not be the right time. So figure out when the right time is. And why.

Again, all this applies to any type of shooting you might do. All five lessons here are applicable to event photography, sports photography, family photography, travel photography, macro photography, basically any kind of photography you can imagine.