A couple of years ago I briefly mentioned in passing that I was going to take some time off to have cataract surgery. The number of emails I got in response to that probably far outweighed the level I got for any other subject that year, and by a wide margin. Some were just well wishing, many related their experience, and still more inquired about specifics because they were considering such surgery. This month, I’m finally having the other eye worked on. So my eyesight should now be restored—at least at distance—to something much more like what I had in my 20’s. [Update: it was restored to something better than 20/20 with both eyes.]

In retrospect, the large response to my original post shouldn't have be surprising. The audience for this site consists mostly of serious ILC enthusiasts and professionals, and that group is highly skewed towards the older and retirement crowd in age. That's not just true for my site, but pretty much for anyone buying US$2000+ cameras; aging population is a problem all the camera companies are dealing with, and they're all trying to find ways to entice the young off of mobile phone camera use, without a huge degree of success so far.

What is a Cataract?

Let’s start off by defining what a cataract is. A cataract is a clouding of the lens in your eye, typically caused by a build-up of protein. This clouding can often have the temporary side-effect of improving close distance sight, but the long-term impacts are that you lose brightness, acuity, and color perception due to the fact that the clouding begins to block light from getting through to the back of your eye. Most articles and doctors will refer to cataracts as a sort of darkening yellow filter, and in a broad sense, that's accurate. Over time, that yellow filtration can turn more to brown, though it may look externally like it's more a blue-gray color.

Cataracts change slowly, so if you're getting yearly eye exams, you'll probably know from your doctor that one is forming long before you sense any change to your vision. But over time, your vision will change as the cataract's impact gets stronger. What signs would you notice if you weren't getting eye exams? Cloudy or blurry vision, an increase in nearsightedness, perhaps a change in the way you see color, problems with glare at night, and sometimes double vision.

The broad generalization is that cataracts tend to appear in your 60's, and half of those affected would likely need cataract surgery by the time they hit 80. But as with all generalizations, there are plenty of exceptions. The young can get cataracts, too, though this is rare.

Cataracts come in several different types. Nuclear sclerotic cataracts are the most common. They form beginning at the center of the lens, which is one reason why your near sight might initially seem better. As time progresses, your lens hardens and the cloudiness increases. Blurring, dimming, color change, and halos are the most common symptoms.

Cortical cataracts start towards the outside of your lens and often as wedges, so they tend to scatter light and the first symptom you might see is glare. Your vision doesn't tend to get better at close distances with cortical cataracts. Posterior sub capsular cataracts form at the back of the lens, which puts them in a clear blocking position for light getting to the inner eye. They often form faster than the other types, and they can have severe visual impacts you're more likely to see. Anterior subcapsular cataracts form at the front of your lens, and can occur due to trauma to the eye. Indeed, traumatic cataracts are often a unique form to themselves, as the cause (burn, chemical, debris, impact) determines the damage to your sight. Finally, congenital cataracts are ones you're born with and are genetic, and would have been caught and dealt with (hopefully) early in a baby's life.

You'd think that would be the entire list, but you'd be wrong ;~). Secondary cataracts usually refer to cataracts behind the lens. You've probably been told at some point to avoid bright sunlight without sunglasses (or at least UV blocking glasses), and that's because ultraviolet radiation can trigger degradation in the lens over time. There's even a rare form of cataract triggered by diabetes, which is called diabetic snowflake cataracts, partly because the pattern in the lens that develops looks a bit like a snowflake.

How Do You Know if You Have Cataracts?

Cataract detection is a normal part of any serious eye exam. The doctor will look at your eye closely with magnification (microscope) and they'll usually put drops in your eyes to enlarge the pupils so that they can better see the impact of any cataract.

Unfortunately, the only solution for cataracts is surgery. However, surgery isn't always imminent.

If a cataract is detected early enough, generally your doctor will simply change your glasses prescription. If your sight can be corrected to 20/40 or better in doing so, this is almost always the temporary approach that will be taken (and partly because of the way Medicare compensates for cataract surgery; a set of measurement bars exist that your cataracts have to get over before Medicare will pay for surgery). Note that once you’re told you’ve got a cataract forming you need to see your doctor regularly—at least every year, possibly they’ll ask to see you more often—as the growing cataract will continue to make ongoing changes to your eyesight. Some cataracts develop quickly, others more slowly. The cataract in my right eye came on far faster than the one in my left, for example.

What is Cataract Surgery Like?

Okay, the time has come for your surgery, what should you expect?

Well, first, the procedure is a surgery, even if it is an out-patient one. As with any surgery, there are risks and possible complications. You'll be asked to sign all kinds of documents after being told all kinds of scary information. Ask questions, make sure you understand everything that's being said, carefully read all documents you're given, and take your time in moving from eye exam to actual surgery.

While there’s debate about whether it is necessary or not, your doctor is likely to require you to be cleared by your family physician for surgery prior to having it. This involves a chest X-ray, EKG, blood testing, and a doctor examination. Essentially a full physical exam. The reason for this testing is that you will be under some form of sedation during the surgery, and both the surgeon and anesthesiologist want to understand your physical condition before submitting you to the procedure. Be aware that all that testing could derail your surgery as your regular doctor wants to deal with an abnormal result first.

The week prior to your surgery you'll be prescribed eyedrops to use, typically two, one a steroid to deal with inflammation (generic: Prednisolone Acetate), the other to prevent bacterial infection (generic: Polymyxin B). With the drops I was prescribed, the routine was four times a day for three days prior to surgery. Don't think you can skimp on this; surgery will go smoother with fewer complications if you follow instructions. You’ll also be taking these eyedrops for awhile following surgery, as well.

Most places doing the procedure will also ask you to stop taking blood thinners and many other drugs in the week prior to the surgery.

Because this is a surgery involving anesthesia, you may be asked to not eat or drink for at least 12 hours prior to the procedure.

The day of the surgery you'll need to have someone accompany you and drive you home, as you'll have been under anesthesia and temporarily not able to see out of one eye afterwards. Most doctors want someone to watch you for 24 hours after surgery, just in case there's a complication. You may be groggy and won't have full vision, so it's important to have someone who can help you during the initial recovery (again 24 hours). The thing that your doctor most worries about is you falling or bumping into something due to the initial vision impairment.

For the actual surgery, you'll be wheeled into a prep area, where vitals will be taken, the anesthesiologist will begin interacting with you, an IV line will be inserted, and a long series of drops will be put into your eyes. One set of drops is used to numb the eye, the other to dilate it. This process takes longer than the actual surgery; it's important that your eyes be in the correct condition before surgery starts.

During surgery you'll be given a sedative—in my case fetanol—via IV. The doctor wants to be able to interact with you, but also wants you not feeling pain or have anxiety about all that's going on around your eye. I was fully conscious and able to follow along most of the way.

Most surgeries these days use what's called small-incision techniques. A tiny cut is made on the side of your cornea and a small tool is inserted that gives off ultrasound waves. This ultrasound breaks up the cloudy lens, and the pieces are removed as they break down. This process is called phacoemulsification. During my surgery I was fairly aware of how my doctor was moving through the eye with the tool and first breaking up and then suctioning off the results. What you see is just an overall blurriness with some bright colors here and there as the tool is working. After removing the debris, an artificial lens is inserted and positioned through the small side cut, then the eye is sealed back up. The actual surgical procedure tends to last just 15-20 minutes.

What’s Recovery Like?

After surgery you'll be taken to a recovery area where you'll be monitored and taken off the IV. You'll generally be given a snack and drink, which given your fasting prior to the surgery I'm pretty sure you'll consume famishly. The anesthesiologist and doctor will both come to double check that nothing is amiss, and you'll eventually be released to the person who accompanied you and who will drive you home. You'll have some sort of a patch over the eye that was operated on, which should remain on for at least 24 hours. The primary reason for the patch is to keep anything from touching the surface of the eye, particularly as you sleep that first night.

The big issue for many immediately post surgery will be balance issues. You'll be one-eyed, and depending upon whether that was your dominant eye and how good its eyesight is, you may have some subtle balance issues initially as your brain adjusts to the new vision data it is receiving.

Issues that are common after cataract surgery include tearing, swelling or drooping of the eyelid, mild headache, sensitivity to light, and double or mild blurring of vision as the eye heals. These all are expected possibilities, and should go away fairly quickly. With my first procedure, I had “good” days and “bad” days post operation, though the general trend was towards better. My second operation was different, and I had fewer “bad” days.

That said, you will notice changes to your eyesight during each day as you recover from the surgery. Mornings tended towards a more blurry presentation in the eye operated on, while mid-day tended to be best. Some of that may simply be the way your recovery works coupled with the impacts of the eye drops you’re taking to help heel the eye.

Things you need to worry more about after surgery are any extreme pain or swelling, significant discharge from the eye, sudden vision loss, a progressive loss of vision, lots of floaters, as well as bright flashes of light or a dark curtain blocking light. In all these cases, you should contact your surgeon immediately to see what to do (see Post Surgery, below).

Generally you will have a followup appointment with your surgeon the day following your procedure, so be sure to describe anything that seems out of the ordinary to you. They’ll look to see that lens is still placed correctly, among other things. You’ll usually need a driver to that appointment, as well, but once the patch is removed and the doctor determines that everything is healing normally, you’ll usually be told it will be okay to drive in the future after 24 hours. That said, it takes up to a month to fully heal from cataract surgery and your vision to be normalized to its new ability.

You won’t be given a prescription for new glasses, should you need them, until the eye has fully heeled and your vision has stabilized. As just noted, allow at least a full month for that to happen. That could mean that you’ll have less-than-optimal vision for something in the period after the surgery. For instance, I work at both distance and near, so post surgery I tended to have less-than-perfect near vision because I was having to use inexpensive Reader glasses instead of a well-made prescription lens.

Post Surgery

One reason why your doctor will ask constantly about floaters and bright flashes after your surgery has to do with the most serious possible complication: retinal detachment. While it’s not a common occurrence in the recovery stages post surgery, it is a very serious one, as a detached retina can cause permanent loss of sight if not dealt with. Lots of floaters or bright flashes after surgery are something you need to be immediately proactive about reaching out to your doctor about, not wait for a scheduled visit. Loss of eyesight can occur within 24 hours of a serious detachment, thus should be considered a medical emergency.

Age by itself makes a retinal detachment more likely. Cataract (or any eye) surgery can be another contributor. Hereditary and other factors enter into the picture, as well. As with all medical consultations, you should make your doctor aware of any family history of eye issues, particularly retinal detachment.

How About Other Types of Surgery?

I described small-incision surgery, because it's by far the most common. However, there are two other types, and they're a little trickier. Large-incision surgery (extracapsular) is used when the cataract is so large or for some reason it will be better to take the lens out in one piece. Recovery from this type of surgery takes longer, and there are a few additional complications that have to be watched for.

If you have large astigmatisms, the doctor may suggest femtosecond laser surgery. As with small-incision surgery, the goal is to break up the original lens, get the pieces out, and then insert a new lens. However, instead of just using ultrasound to break up the lens, the doctor uses a laser to not just break up the lens but to also reshape your cornea.

Are There Complications?

Again, you're having surgery, and thus there are potential complications involved. You need to know what those are. For simple lens, small-incision surgery, the complication rate is very low, on the order of single-digit percentages. Your eye may itch or feel sore, your eyes may tear, and you might have more issues with bright light. However, with some of the more complex lenses that might be inserted (see below), there can be ongoing issues, such as having glare issues at night.

The most common serious post-surgery problems include infections (you'll be prescribed anti-bacterial eyedrops to use for a week or so), detached retina, drooping eyelid, and posterior capsule opacification. In the case of the latter complication, at some point in the future your vision will get cloudy again because the tissue holding the artificial lens gets thicker. Fortunately, there's another simple procedure called YAG that can fix this. It’s another laser-enabled surgery option that deals directly with the opacification.

How Much Does it Cost?

This is a bit of a can of worms, though because of Medicare coverage for those over 65 and for the simplest option there may be no worms in the can at all.

A simple procedure and all followups are usually said to cost between US$1800 and US$3000, depending upon where you have it (outpatient surgical center up through in-hospital). However, a bunch of factors come into play. (You might notice that the first “worm” is a high discrepancy in pricing.)

Let’s start with the simple. Medicare Part B basically pays 80% for the removal of a cataract, the cost and insertion of a simple lens (again, see below), and a pair of prescription glasses or contacts after the procedure. Also, Medicare negotiates a fixed, known cost for everything, which might be a bit different when and where you read this, as those negotiations are regular, some are regional, and Congress sometimes steps in with changes.

Depending on which other Medicare “Parts” you have active and who they’re with, you may have responsibility for a deductible, some additional portion of the cost, co-pays, plus any extra costs associated with more advanced procedures and lenses. For example, Medicare does not usually cover astigmatism correction. For me, I have no astigmatism worth noting, I have Medicare Part A and B plus the AARP Supplemental Plan, as well as Part D prescription coverage. I also had simple lenses installed (see below). My out of pocket cost for my first eye was limited to a single post-surgery visit to verify eyesight after 90 days, and that was reduced via the AARP coverage to something around US$20. I also paid a small amount for the prescription drops that were prescribed (which interestingly, changed in price between the two surgeries not because the drug price had changed, but because my Part D plans’ coverage values changed). Still, all told out of pocket was less than US$50 for the first eye, and I expect it to be about the same for the second.

Even if you had only the minimal Medicare coverage (A&B), your likely out-of-pocket costs are probably going to be measured in the hundreds of dollars for the simpler lenses and procedures (remember, you probably will have two surgeries, one for each eye, separated by some period of time).

The real cost “worm” has to do with special lenses:

Lens Choices

Lens replacement choices—called intraocular lenses (IOL)—are the one area where you need to pay very close attention. Not only are there potential complications and additional costs, but the final results can vary, too.

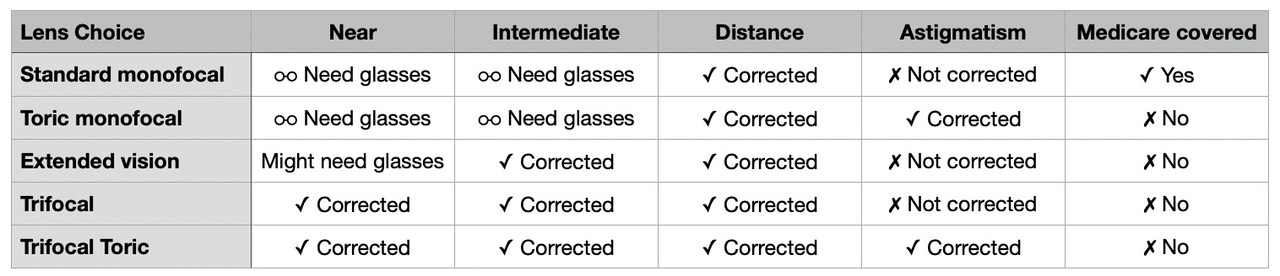

You have three basic choices when it comes to lenses (you may have additional choices within a category): plain, distance-adjusting, and aspherical-correcting.

- Plain (Standard) — The simplest and least costly solution (which Medicare covers) is a simple, symmetrical element (monocular) that will put focus at a fixed position, just like a perfect original eye should. Unfortunately, by the time you need cataract surgery, presbyopia means that the muscles around your eyes can't do focus adjustment very well, so "fixed" becomes an issue. Do you get replacement lenses fixed for reading or for distance? You'll wear glasses still for the opposite choice. I opted for distance, meaning I need glasses for reading. Plain lenses have the least ongoing complications after surgery. Most of your cameras have diopter adjustments that should allow you to use your camera’s viewfinder without glasses after surgery.

- Distance-adjusting (e.g. Extended, or “Tri-focal”)— A multifocal lens is similar to bifocal or progressive eyeglass prescriptions: a more complex lens that allows you to focus at different distances using either concentric or area-based corrections. One such type of lens is the PanOptix lens. Medicare does not pay for these “advanced” optical choices, which may cost you up to US$3500 out of pocket (per eye), and often involve more complicated equipment during surgery, such as a laser. Moreover, these choices tend to produce a higher rate of complications, particularly glare and halos. Also, these lens choices can reduce your ability to see in low light due to decreased contrast sensitivity.

Another alternative to trying to correct the distance-adjusting problem in the eye is to do it in the brain instead ;~). Some doctors might suggest an alternative where one eye is corrected for near, the other for far distance. Indeed, you might have encountered that with contact prescriptions at some point if you had big differences between your eyes. Some people can easily adjust to their eyes being focused different, but it requires training and time to do so, and some people have balance issues that come up trying to do this. I'd strongly suggest you approach the near/far choice very, very carefully. Indeed, at one point I tried a single contact lens (my left eye was still strong at distance) to test a near/far balance. While I could adjust to this, I felt it was too problematic for some terrains I was navigating at the time (think knife edge ridges in mountains and the balance you need to navigate them successfully). - Astigmatism-correcting — Also called Toric correction. If you have a high degree of astigmatism, it can (and probably should) be corrected via the lens element that's put into your eye. Prior to surgery you'll be evaluated on a machine to determine the degree of astigmatism you have, and then you’ll be provided with options for dealing with it. Note that correction for astigmatism increases your costs, as Medicare and most insurances don’t cover such lenses. You’ll likely pay up to US$2500/eye for such correction, and again, the surgery may be slightly more complicated and involve using a laser to help position the lens during surgery. Note that Toric corrections are usually monofocal, so just as with a simple, plain lens, you need to pick a distance (far, intermediate, near) and will need to wear glasses for the distance(s) not covered. However, there are now trifocal Toric lenses available, and these tend to be the costliest option.

My own position on this as a photographer is simple: choose plain if you can, astigmatism-correcting if you are told you need it, and avoid trifocal if you can (due to glare/flare issues, particularly at night). But I have no aversion to wearing glasses—I’ve done so since a teen—and strongly prefer to minimize all possible complications and long-term consequences. Lower contrast sensitivity, flare, and halos are things I avoid in camera lenses, so I’d like to avoid that in my own eyes, too. Here’s a self-test you can take to determine which choice might be best for you.

You should absolutely discuss intraocular lens choice with your eye doctor. Don’t let them push you into a particular choice, and make them explain both the pluses and minuses of all choices so that you can make an informed decision.

Things You Probably Weren't Told

Here are some things that might make a difference in your decision making, but probably didn't know:

- After surgery, your eyesight is going to be variable for a few weeks. Indeed, any reputable ophthalmologist won't provide you a glasses prescription until your sight has settled in, and that can be a month or more after surgery. This is normal, and part of the healing process of the cornea. I had alternating good and bad days the week immediately after the first surgery, which turned more and more into just good days as time went on. After the second surgery, I tended to have slowly improving vision, and not the good/bad bounce I had the first time. However, if you rely on your eyes as much as I do, it's a good idea to schedule surgery for a time when you don't need to heavily rely on them. I carved downtime into my travel, photography, and writing schedules for this.

- After surgery you may have to use "reader" glasses to see close (e.g. computer use or reading), and you're going to find that almost all commonly available reader glasses at retail have significant pin cushion distortion to them (2% or more, and it tends to increase with strength of the correction). Depending upon your original eye state, this might come as a surprise (my left eye has a very slight pin cushion to it naturally when focused close, my right does not). The problem for photographers with pin cushion distortion as much as the readers produce is that we’re looking at rectangular things all the time (viewfinder, laptop screen, desktop screen, etc.). You will notice this, particularly as you move your head in relation to the rectangular thing. With a good ophthalmologist and glasses maker, you can have prescription reading glasses made that minimize such problems and give you a more perfect correction, but those will cost much more than the over-the-counter readers people usually buy. Tip: a decent “reader” is relatively inexpensive and buying a few allows you to do some experimentation. I bought readers from +1.75 to +3 in 0.25 increments, and then learned which value was right for laptop work versus desktop work. You can convey that value to your optometrist and they can write a prescription with that value alongside the other correction (expressed as +175 to +300 after the other numbers). It could be that you need a slightly different correction for each eye, but be aware that you’ll get significant pushback from the glasses maker if the eyes differ: they’ll want to see the doctor’s prescription and signature on that.

- Most lenses used in cataract surgery pass some near UV light; you're likely to see deeper into the high frequency blues and even a bit into UV after surgery. Moreover, cataracts themselves tend towards a yellow filtration—in my case a yellow/green—which means that hue recognition is compromised. After surgery, my right eye did essentially a double-hue shift away from magenta, more so in the blues than the reds. Using Nikon's hue shift capability, I was able to perform some experiments and get a better sense of those numbers: I had a +4-6° shift in blue, -2-3° shift in red. After the second surgery, my left eye is still a little “redder” than my right, though with barely enough hue shift to matter. It is a common reaction for cataract surgery patients to talk about how bright and colorful the world looks after the surgery. You might want to back off the saturation levels you put into your photos after surgery ;~).

- Between surgeries on both eyes, you're going to have issues: (1) brightness between eyes will likely be different; (2) color sense between eyes will be different; (3) balance of focus distance will be different between eyes; and (4) you may need to adjust a lot of things (viewfinder, working distance to computer, etc.). In my case, my eyes had balanced to having one be less dominant prior to the first surgery, but after the first surgery (on my dominant eye), strong eye dominance returned.

- Determining the exact lens to put in isn't absolute science. Because the eye is going to respond to the surgery with some form of healing, and because our brains are adaptive, your doctor can't just put in a lens element that's perfectly equivalent to 20/20 and expect you to see exactly 20/20 vision down the road. This is one reason why you won't see them guarantee "perfect vision" post surgery. You may still need glasses post surgery, even for the distance that your eye was "corrected" to. My right eye was very close to 20/20 post surgery (and a bit better at very long distances), but I opted for prescription glasses that made it somewhat better than 20/20 in the standard office tests.

- Cataract surgery helps with other (medical) problems. After successful cataract surgery you’re less likely to experience a hip fracture, to have dementia, or be in a car crash, plus you’re going to live longer. Yes, those are all supported by statistics measured over a large number of people. Quality of life goes significantly up. Yes, it’s a surgery and has potential complications, but the net positive results—well documented at this point—far outweigh the risks.

Final Words

Cataract surgery these days for most people is a simple, out-patient procedure that has highly positive results. As with any surgery and any body parts replacement, complications can and sometimes do happen, but millions of people in the US get cataract surgery each year, and as just noted, the positives easily outweigh the negatives. You shouldn’t hesitate to start a discussion with your eye doctor about whether or not (and when) to get cataract surgery.

For anyone interested in photography, your eye health is critical to your enjoyment of the hobby/profession. I strongly recommend that you pay close attention to your eyes as you age, and begin the discussion about what to do the minute your eye doctor indicates that they see the start of a cataract forming. The good news is that cataracts are not life threatening and rarely happen so quickly as to demand immediate action. Thus, you have plenty of time to gather information, consult with your doctor, consider options, and make informed decisions.

Since my right eye was done first and I’m right eye dominant, I expected that cataract surgery might have an impact on my photography (I look through the viewfinder with my right eye). I believe it did, and that the results show in my most recent work. I’m seeing the “scene” better, which allows me to make better decisions.

Between surgeries, the biggest impact I saw was that I had to be more careful in post processing. Both the disparity between corrected distance and color discernment changed as my left eye drifted while my right eye had been corrected. I took to closing my left eye from time to time to verify that an adjustment I was making was “correct.” My doctor was willing to immediately tackle the left eye because of the color issues I experienced, even though that cataract wasn’t yet over the usual Medicare bars (there are exceptions that can be made). However, I opted to let things go up to the point where I considered my “sports vision” was starting to be impacted.

What do I mean by that? Well, I learned to photograph sports with both eyes open. My left eye sees the entire scene, while my right eye sees my composition within that scene. Thus, I can see players moving in and out of composition, better anticipate when that will happen, and when I should be pressing the shutter release (peak action). Also, since I roam the sidelines with massive (sometimes out of frame) players sometimes bearing down on me, I need to know when to bail or self-protect. It was when I felt this two-eye approach was starting to get compromised while I stood on the sidelines that I decided to get the second eye done.

So again, the more interest you have in pursuing photography at the highest possible level, the more it pays to keep track of what your eyes are doing and making informed decisions about things like cataract surgery. I hope this article has been useful to you. Strong eyes make for strong photos.

Note: Many hundreds of you have commented on this article within days of posting it. I’m sorry if I wasn’t able to respond to each and every email I received, but trust me, I’ve read and contemplated them all. Some updates (see below) and changes in wording were the result of all this feedback.

Updated: added some post-second surgery notes, more information about drugs and lenses, and corrected a few typos or grammar issues. Added note on seriousness of retinal detachment and being on the lookout for that complication. Added a tip about using reader glasses to experiment with close vision prescription.