News/Views

Tap the Shut and Take a Pho

I was tempted to do this as an April Fool’s article, where I would announce that I was going full on Gen Z with my sites and begin to abbrev almost all long and mult syl words and write only in soc friendly fash.

But there’s a serious topic here, and one that’s actually important to the camera industry (import to the cam ind).

Before I get too far, let me just say that if you’re annoyed by the young calling merchandise merch, or other similar syllabic reductions, then congratulations, you’ve lived a long life. Language changes some with each generation, some more than others. You can live in and hang onto the past if you’d like to, but imposing that past on others is not particularly productive.

Which is sort of the issue the camera makers face. Even the latest and best mirrorless camera is pretty 20th century in most ways. Hierarchical, indirect control, clumsy and crude communication, and even a high reliance on sneaker net. If you think you’re going to continue to sell that to those that grew up with an iPhone in their cradle and an iPad hanging above it, you’re going to eventually fail. To align to my previous sentence, the future is distributed, direct, and communicative.

I started understanding that fully back in the early 1990’s, when my friend, investor, and sometimes compatriot in code Alan Cooper began putting together his seminal book, About Face: The Essentials of User Interface Design (now in its fourth edition). In his work that resulted in Visual Basic and in his help with some of my products, including Tycho TableMaker, his emphasis was in more directly linking user intention with product interaction.

I’ve seen camera companies dabble at the periphery of all three things I mentioned above, so let me bring up a few of those.

Hierarchy shows up in the menu systems and controls of our cameras. Menus went from scattered (really bad) to organized (better) to, in a few cases, growing scattered again (really bad). Fujifilm went from modest and organized to sprawling and disorganized. Sony went from head-scratching to iconic (NEX) to more head-scratching sprawl to finally, a highly hierarchical organization. Nikon is somewhere in between, sometimes pushing a little more hierarchy into the added options, but sometimes—I’ll looking at you Tone mode—creating new anarchy to once settled structures.

If I were to tell you “set your camera to only take images (in focus) of when the hummingbird approached the flower” what would you do? What settings would you need to change, and where are they all located? That’s what you, as a user, want to do. That’s not something you can directly set in the camera. Nikon currently comes the closest with Auto capture, but if you ever dropped into that labyrinth, you’ll know that you’re in for a world of brain hurt. Just get the hummingbird, damn it!

In all that hierarchy we lose directness. Fujifilm recently decided that you needed to directly change Film Simulation, so created a dial for it. Okay. Not something I change much, but I guess some do. However, you can’t just bring up a new dial to directly control every function. Oh, wait, you can do what Leica did, and put a button in the middle of a dial so that you can select what the dial controls, then dial in your choice. Much more direct, and much more flexible.

Nikon goes further than Fujifilm, and just assumes you want to change the look of your image based upon subject. Thus, their Auto Picture Control tries to figure out if the camera is looking at a person, landscape, or something else, and adjusts color, tone, and more based upon that. That’s also indirect, as the camera may not be doing what you actually would have directed it to.

And I’ve hammered the camera companies on communication with other devices incessently for the last 17 years, to the point of even going to Tokyo and presenting what needed to be done to a group of camera executives back in 2011. Seven years later we saw their first attempt. It still isn’t right today, but at least they’re dabbling.

The problem is that these problems were all known a couple of decades ago. That’s long enough for another whole generation of folk to make their way out of the womb all the way to college. And that group grew up with a smartphone, had a tablet or computer at school, has been on social media from the time they could read, and is now looking around for better tools for what they do daily.

As I’ve noted several times recently, the Chinese companies are starting to understand this new generation of customers. Indeed, many of their product designers are at the head-end of that generation in age (or of the previous generation, which had their feet in both the old and new world). If the Japanese companies continue to just do boomer-friendly cameras, they’ll be pushed aside pretty quickly. They’re aware of that, as I see them posturing and again dabbling at the fringes, but they’re going to need to move faster now or else find themselves without new customers at all.

It’s time for a new approach to cameras. Not one that is bogged down in promulgating the film SLR to its extreme, but one that is image centric, direct, and communicative. This is exactly what the smartphones have been doing, and guess what, it’s working. The iPhone 16 isn’t particularly better as a phone than, say, my old iPhone X (what’s with the generation that was only a letter?). But it’s a better camera than my iPhone 15.

Yes, smartphones are more convenient as a carry everywhere camera because you’re already carrying them. But the real reason that smartphones have been collapsing the camera market is that they’re iterating better and faster for the youngest generations while the dedicated camera makers have been slowing their iteration and still targeting the oldest generation.

Tokyo needs to delib the cam and join the next gen.

——————

The About Face book link is to Amazon. As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases.

First Cameras, Now Lenses?

When the iPhone appeared in 2007, the camera market at the time was flooded with compact choices. Slowly but surely the camera makers have been in retreat ever since, almost completely leaving the compact market, and in some cases, even the 1” camera market (e.g. Nikon 1). Most of the remaining dedicated cameras you can buy have now retreated to higher price, larger sensor, mirrorless designs, and there’s no real sign that this trend is over yet.

So when a Tamron executive was quoted by Phototrend as saying “...from a commercial point of view, there are already a large number of players who offer this type of optics [fast primes] and we are rather trying to play the agility card. So we are focusing on our strengths with our zooms,” one has to wonder whether the Chinese prime parade is now turning the Japanese lens makers into retreat, too. (Chinese Z mount autofocus primes now number 59; the number is even higher for the Sony FE mount.)

I’m comfortable calling both these things retreats because it’s not clear what the Japanese camera companies might be running towards. They’re starting to fall behind in software and they are slower to iterate, which doesn’t help, either.

This is one of the things about tech: once a market is proven, you either become the largest and most nimble player, or you will slowly be caught and eventually passed by others. First Mover is always a good position to be in, but only if you know where you’re going next and can get there faster. The longer you linger at any given point—typically to milk the cash from customers without spending it all on new development so your shareholders are happy—the more likely another company just rushes in to fill the innovation void you created. At one Silicon Valley company I worked at, we made the conscious decision not to patent a number of things we had conjured out of nowhere, mostly because we knew that would slow us down and keep us from finding the next innovation before everyone else. If your engineers are always speaking with lawyers, they’re not designing the Next Better Thing.

People ask me all the time to predict what the camera market will be like in 10 years. My quick, snide answer is “Chinese.”

So it isn’t a good thing that good autofocus primes now seem to be flying out of China. It isn’t a good thing that DJI is creating cameras for creators and those that want to view things from above. The US-sponsored embargo on top end semiconductor equipment has slowed the Chinese a bit in SoCs (system on chip, e.g. DIGIC, EXPEED, BIONZ), but it hasn’t stopped them (and will fail to even slow them eventually). It’s absolutely not a good thing that the Chinese seem to have become the lowest cost producer of way more than adequate knockoffs. The canary in a coal mine will be a Chinese acquisition of a Japanese imaging entity. If that happens, the retreat is about to become a rout.

Ironically, the Japanese once stole the imaging baton from Germany (and to a smaller degree, US). Now the Japanese camera industry faces multiple, massive foes—Apple, Google, and China—that are running fast to take the baton away from them. The correct answer isn’t to “retreat.” That’s a stalling action, at best.

Supply and Demand

I probably should have counted all the times that the camera industry said “supply chain issues” were the reason their products were unavailable in recent years. Fujifilm’s President, Koji Matsumoto, just gave another interview in Japan where he again raised the issue.

The interesting thing about all the supply chain claims I’ve seen this past year is that they are specifically unspecific (oh no, I’m channeling Donald Rumsfeld again). Moreover, virtually all of the lack of supply claims came about when the company in question was asked why their latest hot product was not in stock. Older or cooler products don’t seem to have the same supply chain problems, it seems ;~).

The real answer is that everyone battened down the hatches when the pandemic coupled with reduced overall digital camera demand coincided. DSLR volume being eclipsed by mirrorless happened in the 2020/2021 time frame, close to where I predicted it would back in the mid-teens (I tended to write 2021/2022 in the late teens; my original prediction over 10 years ago was 2023).

In 2020 interchangeable lens camera shipments were reported as 67% of 2019. DSLR and compact shipments plummeted more (both about 53% of prior year results). Mirrorless shipments in 2020 were the bright spot at 74% of the previous year, but that’s still not a great number. But not many noticed as we were all much more worried about COVID than what might be happening in Tokyo.

Coupled with lockdown happening at factories worldwide in 2020, yes, supplies were even more constrained than sales. 2022 was a really good year (pent up demand happened as the pandemic released its reign on the world), but 2023 wasn’t another big step forward. Looking at just mirrorless in those years: 2022 was 131% year-to-year, 2023 was 118%. But remember, those numbers were coming back from that big drop. Mirrorless in 2019 was 4.0m units, while “all that growth” in 2022 just brought shipments back to 4.1m units.

My sense is that the camera companies battened down every hatch in 2020, and never really fully opened them again, even today. They’d rather have the problem of their latest product being out of stock than invest capital to increase capacity, which would allow them to come closer to demand. Likewise, if they weren’t investing capital, they also weren’t committing to supply orders at higher numbers. Which in turn would have suppliers not investing capital to expand, and suddenly you have a chicken-and-egg problem: which comes first, more supply orders or more supply production?

It doesn’t help that new cameras require new technology, and these days that means new image sensors and SoCs (BIONZ, DIGIC, EXPEED, etc.). While overall semiconductor fab utilization is not at historic levels, if you want new small process (SoC) or new image sensors, the story is a little different. Memory, not a problem. New near smartphone-level SoC, problem. Rumors have it, for example, that Apple alone has committed to 100% of TSMC’s smallest process size production for the coming year.

The other option here is to build inventory. Take Nikon, for instance. They seem committed to push EXPEED7 down through their entire lineup. Great, so maybe a lot of chip orders now might break a log jam. But everyone’s inventory reluctant, too, so Nikon really wants scheduled EXPEED7 delivery that matches their estimated final product delivery, which tends to be on the conservative side. The old just-in-time thing that tripped up everyone during the pandemic, despite the reduced final product demand.

Which brings us to this: “how good is Tokyo’s new product sales forecasting?” I’d tend to say “not very good.” I believe they intentionally ignore really high initial demand believing that they’ll just have a viral/hot product for awhile. I also believe that they incorrectly forecast the “tail” of sales for all their existing products, too. I won’t identify the company or product, but I was recently told that one product did really well out of the gate (and had clear backorders), but that demand tapered faster than they expected, which forced them into putting it on sale earlier than they expected to.

I spent a little time looking at retailer stocks here in the US while preparing this article. Canon RF? Pretty much every camera, even the most recent R5 Mark II, is in stock. Fujifilm XF? Bodies in stock, some body+lens kits seem to be out of stock. Nikon? All bodies seem to be in stock. Sony E/FE? Seems like everything is in stock. (By “in stock” I mean that I could easily find multiple dealers I could get a product shipped from today here in the US.)

Which brings us to another interesting angle that isn’t written about much: Fujifilm’s Matsumoto-san was actually talking about the Japanese home market, not global. It seems that the camera makers are once again putting their available inventory first into the markets where they make the most money and where there is higher demand (read: economic market strength). The value of the US dollar versus the yen and the clear economic growth in the US is one of the reasons why the American market is well stocked at the moment.

Thus, many of the “apology for not delivering product” messages you see from the camera companies tend to be regional ones. So maybe it’s not demand exceeds supply so much as it is just more micromanagement of where new products are sold as they are built. That’s not to say that there aren’t still a few products that are in short supply. The Fujifilm X100VI is still unobtainium here in the US, for instance. (Don’t worry, by the time all the other makers respond to that camera with their own versions, the X100VI will be obtainable.)

Overall, though, I don’t sense any real supply shortage that’s causing demand not to be met. It’s a completely self-goal on the part of the camera companies.

Interesting Things Written on the Internet

Updated: see bottom.

"I don’t know if the GFK data is for France or Europe only, or if it is about worldwide data. But 40% market share outside of Full Frame might not be a horrible position to be in." -- FujiRumors in reference to interview in Phototrend that Fujifilm's share of the non full frame market is 40%.

"Fujifilm Says it Owns 40% of the Non-Full Frame Camera Market" — Petapixel headline referencing the same interview

----------------

First off, let me say that I don't think that the 40% claim is worldwide. It's not even clear if it's anything other than in France (e.g. not a Europe claim).

But let's assume for a moment that it is a worldwide claim. For the last full year mirrorless sales we have a total of 4.76m units, and Fujifilm was 380k of that. If you run the math, this claim would further assert that full frame is 80% of the sales in mirrorless. Fujifilm would thus have a 40% share of 20% of the market, not exactly a claim I'd want to be making. Indeed, if you're missing 80% of the market, you're basically just missing.

Again, I don't believe the claim is usable in order to assess what is really going on in the mirrorless market. Most certainly, Canon didn't sell 1.57m full frame units to Fujifilm's 380k!

So just like with the NPD numbers in the US, the TSR numbers from Japan, the GFK numbers in (probably part of) Europe are mostly being used these days as limited bragging rights. They continue to be sliced in ways that favor the bragger. Because these marketing research firms—NPD, TSR, GFK—sell their data to the companies they cover, every company then looks for ways they can "cleave" that data to make a claim of dominance or success. The public can't see the data upon which those claims are based, thus should be skeptical of them.

The data I'm looking at closely these days is the detail in each company's quarterly/annual financial results and other disclosures. Nikon is the most transparent in that, but with some deeper sleuthing you can get reasonable handles on the top four makers (Canon, Fujifilm, Nikon, and Sony). What I'm looking mostly at are two figures: unit volume growth and total revenue growth. Right now, those have been growing in strongly positive ways for the middle two companies just mentioned, not as strongly for the outer two, though growing. This coming year (2025) is critical for Canon and Nikon, as they will have essentially jettisoned their DSLR lines. Nikon seems to be predicting little future unit growth and lower future revenue growth.

As I've been pointing out, I'm having a difficult time believing that 2025 is going to be a growth year for interchangeable lens cameras at all. I don't currently believe that mirrorless will fully make up for the coming lack of DSLR sales. Which means that the overall market has once again has "peaked", and either will be on a plateau or on a downslope in the near future.

We can debate what that would mean. And it likely will mean something a bit different for each company. For example, a flat or declining ILC market has these company-by-company implications, in my opinion:

- Canon — Canon has been pursuing the "biggest market share" approach for decades now. Their target seems to be 50% of unit volume. The problem for Canon is that they will have to be the price leader across a very broad product line to continue to accomplish that, which means they have to either (1) accept lower margins or (2) take more cost out of their product. I'd bet both will happen. I personally believe that Canon is pursuing more of a bolster-our-ego strategy than a maximize-our-return strategy. Only 21% of Canon's most recent sales came from Imaging, though it was their second highest profit center. Do remember, though, that Canon's imaging group contains far more than just the cameras you and I buy, including what Canon calls networking cameras. Prediction: R officially starts at US$399 or less, and more instant sales are used to goose volume. No ILC market share gain in 2025, possibly a small loss.

- Fujifilm — I used to write that cameras were somewhat of a hobby business for Fujifilm. With the popularity of the Instax system, that's no longer true (Fujifilm has more revenue from instant photo products than digital). The forecast for their current fiscal year is that "imaging" will be about 16% of their sales and over a third of their profit (operating income). That level in a company as big as Fujifilm means that they're now exposed to changes in the camera market. That said, digital cameras, mostly mirrorless, are only 43% of their current "imaging" sales, so modest changes in market volume probably won't impact them terribly. However, model proliferation would be a problem for them in a flat or declining market, as it lowers margins. Noticeably, Fujifilm doesn't call out profit from digital versus the Instax/film side. Everyone's suspicion is that there's a mismatch in gross profit margin between the two. Prediction: they continue to iterate APS-C models, though the returns in doing so are minimal. Minimal market share gain, if any, in 2025.

- Nikon — Their cautious, mostly top end approach has netted them real mirrorless growth, both in units and profits. A flat or declining market will make that unsustainable with just the Z System (DSLRs and compacts gone), which partly explains the RED acquisition. Nikon wants to be a broad, diverse company, and has in recent years invested in and expanded into many other areas. How's that worked out? In their most recent quarterly results the Imaging group provided 51% of the sales, and was the only one of their six businesses to make an operating profit. Oops. (Full disclosure: for the full fiscal year, they expect all but one of their businesses to be profitable.) Prediction: RED will be a bit of a distraction (video lenses are needed, where the product lines meet needs to be determined), so we're likely still on the one or maybe two new cameras a year with a little fill in on lenses stream now. Minimal market share gain, if any, in 2025, and to do that will necessitate more aggressive sales.

- OM Digital Systems — Reliable financial information leaked out of Japan this year about OMDS: not profitable, though the annual loss has reduced. Coupled with their continued loss of market share (now down to about 3% of the mirrorless market), it's difficult to see how OMDS manages to bail all the water out of their sinking boat. 2024 for them, so far, has been revealing: a firmware-like update to their major camera, a rebadged lens, and a lens designed and built by Sigma moved to the m4/3 mount. I don't see how OMDS gets any additional investment/capital until they fix the leaks and get to at least minimal profitability, even in Japan's liberal investment community. No significant new products means no growth, so we're now seeing the Pentaxification of the Olympus cameras. Prediction: the R&D dollars for breakthrough products probably isn't there, so modest new offerings, if any. And that's best case. Market share loss in 2025.

- Panasonic — I'm more than a little surprised at Panasonic. After getting a clear ROI goal many years ago by their corporate president, they don't seem to have truly fixed and clarified their lineup to meet that goal. It's possible that they're getting by with very regional targeting. Panasonic is a hugely diverse company, making everything from batteries to air conditioners, with a lot of mostly consumer products in between. Their loyalty to a lens mount across their digital camera offerings (still and video) is just as diverse—EF, PL, B4, L, m4/3—which I pointed out was going to be a problem for them over a decade ago (because Sony went all in on a single mount). That I can still buy a US$7000 Super35 camera from Panasonic with a Canon EF lens mount just seems mind-boggling. Where the L-mount replacement for that EVA1 is, who knows? In the highly competitive mirrorless game, Panasonic is currently paddling in place while watching their former partner slowly sinking alongside them (see previous). Can they keep that up in a flat or declining market? Difficult to say, but if Canon goes to spot sales to keep their market share, that increases the difficulty. That said, I should note that Panasonic just made the claim to be third in mirrorless in the French market to Phototrend's interviewer. My guess is that, if examined closely, that would be for a time period following recent product introductions (e.g. S9, S5D, and GH7 intros). Prediction: more of the same, which will seem scattered. No market share gain in 2025; possible loss.

- Sony — If Panasonic is diversified, Sony is even more diversified. "Still and Video Cameras" (of all types) were less than 8% of their overall sales in the most recent quarter. To put that in context, sales of image sensors and semiconductors is something like 14% of Sony's overall sales. I'm not one to think that Sony will pull out of a declining camera market (as they did with laptops, for instance). First, they've been growing overall in their group, and second there are too many synergies that cross over into their other divisions. But a flat or declining ILC category does raise a question that I don't know the answer to. Does Sony (a) seize the opportunity to take over first place in market share, (b) manage things as they have been, or (c) carefully manage and whittle product line to ROI as volume declines? I don't know. I'm not sure Sony has a clear answer to that. At the moment, it appears that (b) is their answer, as that's been working for them as DSLRs disappear. Prediction: Sony will start picking sub-categories they want to win, and start rationalizing their lineup more. Minimal market share gain in 2025.

Regardless of the above, nothing has basically changed about all the market share talk. Once the full 2024 numbers are in, we'll see another full round of brag claims, each of which is difficult to verify and specific to a particular time frame, region, narrow category, and/or other unspecified limitation. This is what I call Kindergarten Marketing; my toy's better than yours.

Update: It struck me that Fujifilm was vague on what they meant by 40% market share. It's possible that they meant "by value" instead of "by unit," which would be quite disingenuous since the GFX bodies would distort the results. Then BCN published their "top 50 sellers" in the Japanese market for September. Hmm. 40 non-full frame cameras, of which Fujifilm could claim #19, #26, #34, and #44. So in Japan it's inconceivable that Fujifilm's claim would be even remotely accurate for volume. That leaves me with two possibilities: Fujifilm is doing really well against full frame in volume in France, or Fujifilm didn't disclose that they meant "by value."

Behind the Scenes

I've written about this before, but this week I got an email that was so blatant, I believe it worth repeating prior to this holiday season. What bothered me? Well, this:

"Hello, if you are interested in writing a 5 stars review for [Chinese maker] lenses on Amazon, please email me. We will refund you via PayPal after review."

It should bother you, too. Basically, this type of promise skirts around Amazon's policing, as you could show up as a verified purchase review while behind the scenes out of Amazon's view something else is going on. This gaming of reviews has long plagued pretty much every buying site that has user reviews. Making said reviews unreliable.

I get multiple offers for play-to-pay reviews every week now. More often than not, they're "we'll let you keep the lens if you review it positively." Many are "we'll let you have early access to the lens..." However it seems like the intensity is increasing, and the ask from the reviewer is getting higher.

My sites have a strict policy: while I'll take a loaner or free sample from time to time, I fully identify when I did, and there is absolutely no quid-pro-quo behind the scenes; I insist on being to write freely about what I find. Several companies have withdrawn their offers of loaner/free products when they learn that there's no guarantees on what I'll write, and that they'll not get a preview of it, either.

Given how pervasive the "please help us cheat" requests are becoming, I'm strongly considering going full Consumer Reports (all reviewed products purchased anonymously). That, however, either raises my costs of doing business, or it means I need to review fewer products. I'm leaning towards the latter. That would also mean my reviews get delayed further, as buying a product through something like NPS Priority Purchase—which I usually do for Nikon products—would not be anonymous.

Anywho, the main reason for writing this article is a bit of a warning: if you're going online to buy things this holiday season, I'd say that you should probably avoid paying any attention to the buying site's user reviews. Moreover, be careful of even independent site product reviews. So many games are being played behind the scenes now that you need to verify the integrity of the reviewer in order to trust the review.

The Upcoming Format Change?

If you're as old as the hills as I am, you probably grew up thinking that photos were to be taken in the 4:3 aspect ratio, mostly horizontal (vertical grips didn't exist back in the stone age when I still lived in a cave). 4:3 was the "small" format from the 120 roll film format Kodak established back in 1901. The "medium" size was 1:1, while the "largish" size was 3:2. Oh dear. Aspect ratio confusion from the beginning.

The 135 (35mm) format was introduced by Kodak in 1934, and is essentially 3:2 in aspect ratio. Confusingly, you could get 4x6" (3:2) prints from the lab from your negatives, or larger 8x10" (5:4) prints (as well as other 5:4 sizes). To this day you'll find that picture frame sizes in stores tend to be in that 5:4 aspect ratio, despite the fact that none of the actual current default capture sizes have that same definition.

In terms of that default capture, digital has given us 4:3 (4/3, m4/3, and some medium format) or 3:2 (1", APS-C, and full frame), plus lets us crop the capture in camera variously, typically 1:1, 5:4, and 16:9, but some other oddities, as well (18:9 anyone?).

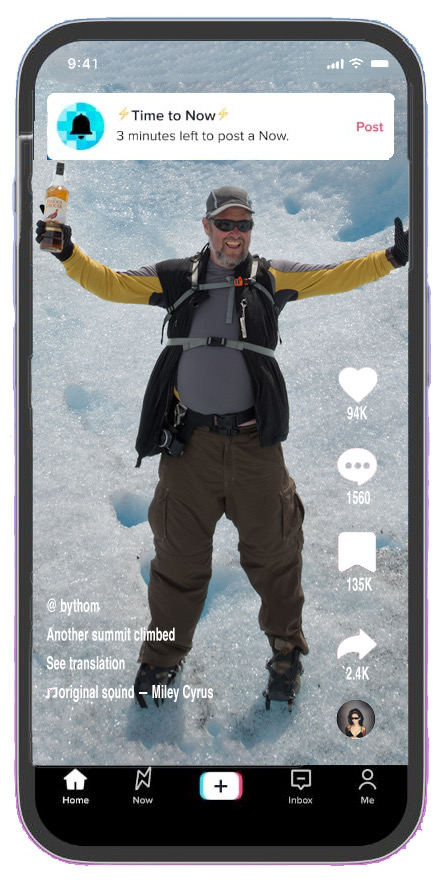

The world has moved on from paper, and we have a whole generation who grew up with thinking the world is 16:9. Or more recently due to TikTok, 9:16 (see screenshot at right).

Pentax was the first to give a nod to the TikToking world, curiously with a film camera called simply the 17. Of course, it doesn't quite line up correctly, being 17:24, which is a bit short vertically.

Rumors now have it that Fujifilm has decided that they can create the next viral camera with the new generation by taking a 1" sensor and turning it sideways, basically providing 9:16 stills and video in a small compact camera.

Fujifilm apparently noticed how many who bought their last viral hit, the X100, were using it vertically instead of horizontally. I, too, noticed that at the most recent WPPI conference, where a number of instructors and influencers had just gotten their (40mp!) X100IV cameras and seemingly were always turning them sideways. That's sort of awkward for a dials-controlled camera, as the dials then flip away from your controlling hand, making you either turn the camera back or reach over it to make a change. Moreover, I can't believe how many I see one-hand the camera while turning it vertically, which compounds the problem.

This potential new Fujifilm camera, if it appears in 2025 as rumored, would be another example of something that seems to be finally happening in Japan, which is to begin fully embracing the fact that images, and even videos, are shared on smartphones now, not printed. Indeed, pretty much every digital display is 16:9 these days, so it isn't just sharing images on smartphones that's necessary, but also tablets, TVs, laptops, and even computer monitors.

Here's the rub, though: the reason why vertical 9:16 works better on smartphones (and to some degree tablets) is because of the way you hold them normally. You don't try to grasp the sides that are 16 apart; instead your hand grasps better using the 9 apart sides. However, for laptops, computer monitors, and TVs orienting them horizontally plays better to our vision attributes.

So in case you haven't already figured it out, the gating element on that possible Fujifilm TikTok100 is actually a very tricky problem: how do you orient/use the displays? Selfie is still a significant thing with this group, so how do you orient a flip out display? Is it now flip over?

The camera makers have spent 70+ years "perfecting" (and bastardizing) the "grip it and push it against your face" design that pretty much makes them horizontal (unless they extend the body to nearly square in shape with a vertical grip). The smartphone makers, on the other hand, have "perfected" (and bastardized) the "hold it two-handed in front of you" design (which, by the way, only works with pre-presbyopic eyesight or bifocals; thus the reason why the young have no problem with it but the elderly often do). Note that DJI, of all companies, has actually figured out how to solve the display problem: witness the DJI Osmo Pocket 3, with its rotating screen (and rotating camera, for that matter).

We need new, young blood entering the serious photography (and video) markets. For the camera makers to continue to succeed, they need to cater to a group that grew up with a smartphone in their pocket and the accompanying sharing apps. Right now it's a pretty big leap from 9:16 1080P-sized capture to the 3:2 8K-sized capture the camera companies really want to sell. Not just in price, but also in "usability" from the standpoint of that younger crowd.

It's pivot time for the camera companies (literally in the case of the Pocket 3 ;~). They either embrace what's really driving the imaging business now and give those users higher capability options with more control and potential, or they can watch us old digital dinosaurs die off and their existing camera businesses decline to nothing.

Bonus: In case you haven't been paying attention, I've been using 16:9 as my aspect ratio for quite some time now. Every now and then I'll get someone sending me email saying that they "want the full photo" instead of what they presume to be a horizontal crop. It is often a horizontal crop, but my viewfinder has long been set to show the 16:9 aspect ratio for framing. Some of my clients don't care, as they're mostly social media to start with (though some edit my work further to Instagram's 1:1). Only the newspapers seem to complain now, though they should pay attention to why I use 16:9 on that front page image: doing so places the image fully "above the fold" on a desktop screen, with room for the most recent content still visible below it.

Which brings me to an aside: I'm in the midst of considering redesigns for the sites. I've learned to hate the "doom scroll reveal" designs that everyone seems to be using today (example: Apple). Yes, that works well for small displays, such as smartphones, but the site designers rely far too much on a full frame banner image and title to do all the initial work; to see anything meaningful, you have to doom scroll. That's not particularly useful for a site that is dealing with news and constantly changing content. I don't believe in wasting my readers' time: you can come to my sites and see if there's anything usefully new at a glance. If not, doom URL to your next favorite site ;~).

More Questions Asked (and Answered)

"Will Nikon introduce a global shutter camera?

Yes.

The only real question is "when?"

I've been following Nikon patents for three decades now, particularly ones pertaining to digital imaging. Nikon has quite a few patents in the global shutter arena, with one of the most interesting one being a hybrid global/rolling shutter patent (just resurfaced by Asobinet in Japan). In that updated patent, the original of which is now eight years old, Nikon outlined how to create a global shutter for areas with motion, while a rolling shutter was used for areas without motion. In essence, that particular patent is trying to mitigate the downside of both types of electronic shutters simultaneously. To put it simply, an AI autofocus system would inform the sensor as to where to place the global shutter regions.

It's unclear to me just how well this hybrid approach would work in practice. A bird at a distance that only impacts a small part of the frame would seem like it might be a good candidate for such a system, but the 250-pound running back that's filling my frame and about to plow into me doesn't seem like it would. Moreover, there's the issue of near static subjects with flash. What I don't think I want is a system that's worst case for both rolling and global shutter impacts in some cases, but not all. I'd rather just have a global shutter with reduced dynamic range (see next question).

Overall, Nikon is taking small steps towards global shutter. The Z8/Z9 stacked sensor and the Z6 III partial-stacked sensor try to bridge the gap, and do a pretty good job in doing so. Still, I can see Nikon moving additional steps forward and eventually having a fully global shutter. It's really just a matter of time. It's also clear that Nikon's sensor development team is actively pursuing a number of different approaches, which is what I believe they should be doing.

"It seems that all the new cameras being introduced are tending to go backwards on dynamic range. Is that now something we need to expect?"

Maybe. What happened in APS-C and full frame is that somewhere around peak camera (2011/2012) we hit a point where image sensors did an excellent job of rendering the randomness of photons without adding any real extraneous digital-caused noise. Since then we have not had a sensor technology advance that would do a better job of capturing the randomness of photons. I get slightly conflicting estimates from different engineers about what is possible using the current photosite designs, but in no case would that give us more than about a stop more dynamic range from where we were. In essence, efficiency is the primary remaining barrier, and that has the problem that Bayer filtration is the primary reduction of efficiency now.

Sensors shifted from trying to provide more dynamic range to providing more speed. For instance, the original 24mp full frame sensor used in the D600 was remarkably good at dynamic range, at about 11.5 stops of useful range at base ISO (100). The current Z6 III 24mp sensor trails the D600 by about a stop at base ISO, though with the dual gain bump, it does ever so slightly better starting at ISO 800 (and retains that without using scaling or noise reduction through a much larger range of ISO).

What changed between the D600 and Z6 III is speed, both within and pushing data off the sensor. Electrons are pesky little devils, and if you heat them enough and move them rapidly, they start generating forms of digital noise, and that noise starts impinging on useful dynamic range.

The reason my answer to the question is "maybe" is for multiple reasons: (1) process size reduction has an impact, and most image sensors aren't close to what's possible in that regard (CPUs and SoCs dominate the fabs that are capable of really small process); (2) on chip noise reduction—Canon uses this approach—and other techniques can mitigate the digital noise; and (3) it's possible to imagine other approaches (if I were a betting man, I'd guess professor Fossom's QIS approach will come to fruition before any boundaries are broken with traditional CMOS sensors).

The real problem is simple, though: lack of dedicated camera sales volume restricts large sensor R&D. Mobile devices, autos, and security systems are where the image sensor volume is, and thus breakthroughs will happen there first, as the cost of making a big tech change can be spread across more units. Large sensor (APS-C, full frame) cameras get more iterative approaches now as those cost less to produce. Most of that iterative work has centered on speed, as the current goal seems to be trying to get to a true global shutter sensor without compromising the dynamic range further.

Ironically, dedicated camera users are now dependent upon two outliers from pure photography, video and smartphones. Video has been driving the speed issue. Don't forget that speed gives you a better viewfinder and focus system. Meanwhile, smartphones are driving additional improvements that don't get talked about a lot, such as crosstalk.

What's Left for the Camera Market?

For years the general conclusion has been that the smartphone has been gobbling up more and more of the camera market, starting originally with casual snapshots and now often suggested to be any photo possible with a mid-range zoom (e.g. 24-70mm). I certainly agree with the former contention, but not exactly the latter.

As it turns out, smartphones have still left a largish arena for dedicated digital cameras to play in, though no single Japanese camera company seems to have figured out the breadth and depth of that available realm.

Let me start of by saying that smartphone cameras have gotten considerably better over the years (as expected), but the "tuning" of them tends to be narrow. By that I mean that the real goal of most tends to be how good the images look on the device or in social media. There's a lot of behind-the-scenes shuffling and manipulation of the captured data that's all predicated on that assumption of output.

For instance, to deal with the random nature of photons while photographing in low light, the smartphones these days look at adjacent moments for non-moving backgrounds and use machine learning or artificial intelligence to "correct" moving elements in the scene. Since they're already dealing with a video-like stack of images around the moment, they'll also use that extra information to inform "exposure" decisions, bringing up dark areas compared to the brightest range. Coupled with HDR displays and HEIF, the results can look really darned good on the device. Indeed, often better than straight-out-of-camera JPEGs from dedicated cameras.

More recently we've seen the addition of more pixels in smartphones (using the same or similar area), often with a quad-pixel design (basically Bayer, where each Bayer color is broken into four sub pixels). This gives the intelligent engines within the phones more pixel density with which to determine detail, at the expense of color information for that detail (partially made up through new demosaic patterns).

My current assessment—made mostly with recent iPhones—is that we're at the stage where excellent 12mp images can be taken in most situations from about 13mm to 120mm, and perhaps something approaching 24mp quality level can be obtained in certain situations, though mostly centered on the 24mm focal length. (I'm using "equivalent to dedicated larger sensor camera" focal length numbers here.)

Yet I wrote earlier that there's still a largish arena for digital cameras to play in, so what did I mean by that? Let me highlight some of the areas still relatively protected from smartphone cannibalization:

- Timing. While all digital camera shutter releases have a tiny bit of lag to them compared to the actual capture moment, with practice you can be incredibly precise at capturing "the moment." I had someone on the football sidelines recently tell me that they don't use a second camera anymore for the close action, because they just take out their smartphone. Okay, but are they capturing peak moment any more? I don't think so based upon observing their output. Good thing publications seem to only want "jubes" images now, as those often have plenty of usable moments to them (as opposed to the exact moment of the catch with the foot dragged inbounds). But in terms of "timing" a sideline event, I'd rather try to do that with the Fujifilm X100VI or similar camera than my smartphone still. And, of course, my Z9's excel at that.

- Telephoto. The iPhone is up to 120mm in focal length now, though I don't find that to be as good a lens and final capture as for the other two capabilities (wide, midrange). Pixel density with "reach" is still dominated by larger sensor cameras; it's pretty stunning what even a Coolpix P950 can do, though Nikon really needs to refresh the firmware in that camera with some of their more current knowledge. It's not surprising that Nikon has been emphasizing getting the telephoto lineup "right" with their mirrorless system, particularly when you realize that a lot of folk who want #2 also have a need for #1.

- Size. I've seen some iPhone images printed large, and they're pretty darned good (though highly curated). However that tends to be an image that's lower on fine detail and more about overall subject impact. And as with most large images we encounter today—e.g. backlit large displays at the mall—the phone images do show their weaknesses if you examine them too close when displayed large. On the video side, 4K is a fairly low bar, and the recent smartphones manage this quite well. 8K is where I see some clear differences between what the phones are achieving versus dedicated gear. Of course, who has an 8K display and can afford 8K/60P data storage?

- Bokeh. It's no surprise that the topic of bokeh has gotten a lot more lip service lately. The small capture size and lens constraints of smartphones put limitations on what they can do directly. Moreover, the smartphone attempts to use depth information to build out-of-focus areas artificially still pretty much gives itself away on examination, at least to my eyes. Fast lenses on large sensors produce the type of out-of-focus areas we have a long history of experiencing (much like inter frame blur with video), and tend to thus prefer.

- Control. While smartphone camera apps can be found that give you more control over what's happening—Halide for the iPhone, for example—they don't come close to the fine-grained control and nuance that's available these days on most dedicated cameras (which was one reason why I complained so loudly about the lack of control customization on the original Nikon Z models). I'm not sure that the camera companies exactly grok what we want to control and why, but if they want to survive, they'd better.

It's clear to me that Nikon has considered most (if not all) of these things as they tried to put some distance between themselves and the smartphone makers. Coolpix: (mostly) gone. Dumbed down UI: gone. Lots of telephotos. Faster prime lens base set. The Z9 is 45mp because of #3, plus has a stacked image sensor supporting #1, and has the most exposed control (#5) of any previous Nikon, for example.

But consider the Fujifilm X100IV using the above criteria. Timing: check. Size: check. Bokeh: sort of check. Control: check. It only misses on the telephoto bit. Not all dedicated cameras will hit on all five, for sure, but that's probably fine as long as they do a good job of excelling on two or more of the others.

I should point out the obvious. If you're a well-established smartphone photographer and have hit the limits of what you can do, what are your choices? (1) Wait for smartphones to get better. (2) Buy a dedicated camera that gives you more headroom on what you can create. Instead of fearing the smartphone cameras and running away from them, the dedicated camera makers should be embracing them and preying on their customer base to move up.

As I've written for well over a decade now, the camera companies need to better match the smartphones in terms of getting images to social media, as that's where most images are at least initially shared now. If the photographer uses HEIF, they can even match the HDR characteristics on the small displays. Why is this point so important?

Well, take that sideline photographer and his smartphone: one reason why he's using it is that he can push an image to his agency immediately, for release on the wire services almost instantly. He has (mostly) better access to the play and athletes, so he can still get a better image than the person in the crowd can with their phone. What I've objected to in the mobile device linkage of pretty much every dedicated camera is that the minute a smartphone user can do it as well and faster than I, I lose (and so does the dedicated camera maker).

So these questions arise out of the above:

- Exactly how many units can be sold that fit into a majority of those criteria? 3 million a year or 6? It makes a difference, because unit volume will dictate R&D expenditures, and if R&D goes down at the camera makers, it's game over: the running away from smartphones goes to narrower and narrower niches, and the smartphones continue to gobble upwards.

- Which camera makers have really figured this out? As I note, I'm pretty sure that Nikon's thinking pretty much is (now) aligned with the above. Even the acquisition of RED and their >4K video cameras fits in the above criteria. On the other hand, I'd tend to say that Canon is still "executing as before." Their drive to maintain a 50% camera market unit share means they have to play extensively at the low end that the smartphones keep nibbling at, and I'm not seeing how they are going to stay competitive at that.

- Can anyone market those criteria well? So far, my answer is basically no. I sometimes see a statement or two in a press release or product introduction event that speaks to these things, but it's usually buried in other statements. Go back and re-read any dedicated camera press release in the past year and evaluate whether it speaks to the five criteria I list or not. QED.