The CEO of Sony Semiconductor was quoted last week by Nikkei as saying in a briefing session: "We expect that still images will exceed the image quality of single-lens reflex cameras within the next few years." Nikkei's headline says that year is 2024.

Of course, there's a bit of self-interest in that statement, as Sony Semiconductor is currently on a campaign to get more image sensor design wins in future smartphones. This is a bit of a reversal from the recent past, when Sony suggested that smartphone image sensor usage would taper off and no longer be as much of a growth driver for them.

The devil's in the details, as usual. While image sensor improvements will play some part in smartphone image quality increases, the real improvements come mostly from extra processing, as Apple and others have been demonstrating for years.

Too many photo sites are unfortunately promoting Shimizu-san's words as "the demise of interchangeable lens cameras" (ILC). Sorry, but no.

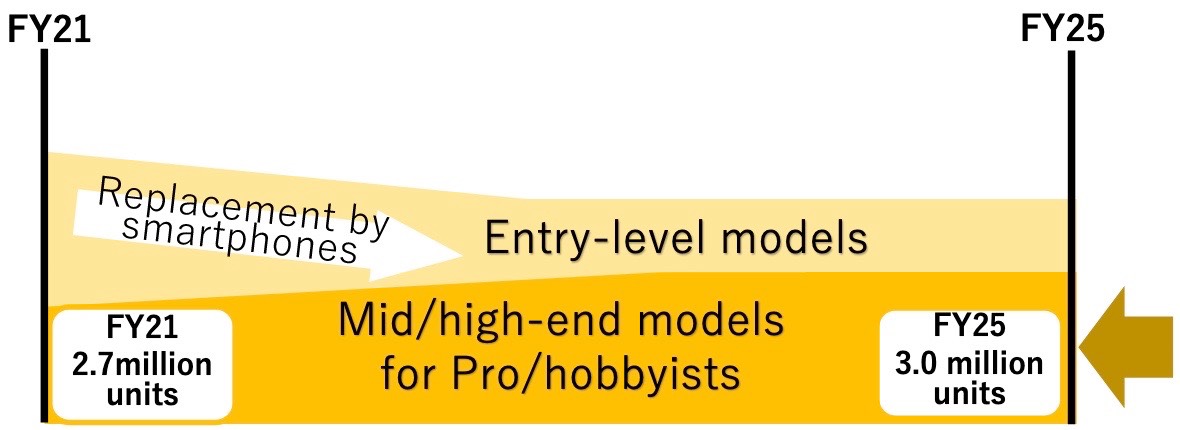

Actually, Nikon's Investor Relations presentations last week told us what the real situation is likely to be with ILC:

Essentially, the higher end of ILC holds its own, with little to no growth over the next four years (note that someone at Nikon corporate was just as confused about their fiscal years as most of the press: the actual years being referred to here should be labeled FY22 (which ended with 2.7m high-end units on the year ending March 31, 2022) and FY26 (which ends in March 2026).

If you go back and look at my predictions from several years ago, I wrote that the ILC market was likely to bottom out at 4m units (and that was just a modest update of my 2009 prediction on an upcoming "smartphone squeeze"). It appears that Nikon now agrees with me. ILC is headed for a similar situation that happened in the last decade of film SLR dominance: stagnated sales levels.

There's a difference this time, however: in the 1990's sales were near flat or slightly declining across all levels of ILC, from entry-level to pro. This time, only the entry-level is going to be slowly wiped out by smartphone competence, while the higher end cameras will continue on with stagnated sales levels.

What's that mean for you? I'd put it this way:

- Sub US$1000 ILC models will slowly disappear over the next five years, even if we adjust the US$1000 number for inflation along the way. The development costs just can't be recovered well with declining volume. For Nikon, in DSLR terms that means the D500, D780, D850, and D6 would be the only models that could survive out to 2026, and even that list will likely be winnowed in the next four years. In mirrorless terms, it means that any Z50 update has to hit higher (e.g. Z70 level and US$1400+), and it and the Z5 II would be the new bottom of the lineup. No Z30 is likely to appear, though I wouldn't be surprised to see a Zf come out instead of a Z5 II at the low full-frame price point.

- The success of the A1 and A7 updates, the R6/R7, and the Z6 thru Z9 models mean the camera companies are going to put most of the development at those levels and higher. By "success" I mean return on investment. Nikon, for instance, can build a Z7 II far less expensively than a D850, so their margins went up considerably for essentially the same specification of camera. US$2000 and up cameras are what is being targeted in that pro/hobbyist market where the customer is still buying.

- APS-C models really have to take on the model that the D300 originally established: nearer to full frame performance characteristics but at the reduced cost associated with the smaller image sensor*. The Canon R7 and the upcoming Fujifilm X-H2s are just the first of those.

- Video will continue to be a key development area, as (again from Nikon's presentation statements): "the number of users motivated by 'video shooting' has more than tripled over the past 6 years." The tricky part here is that the (lack of) ease at which you can record video on an ILC and get it directly to social media is holding up more adaption by younger users, which is going to be a problem that is increasingly important for the camera companies to solve as their older, established customers die off.

- It's not surprising that you're seeing Canon and Nikon emphasizing frame rate, sophisticated focus, and telephoto lenses in their recent offerings. These are things that smartphones have a tougher problem matching. Sure, a single still image taken of a landscape or even indoor scene can be improved by solid computational add-ons in a smartphone. But 45mp, high dynamic range, clearly focused, telephoto-necessary imaging is still easily the reign of ILC. It's not surprising that six of Nikon's first Z-mount lenses and eight of Canon's initial RF lenses are substantive telephoto offerings. We'll see more of that, not less.

*As I've been writing for over 15 years, the image sensor is the most expensive part of an ILC, and you simply can make an APS-C image sensor at at least 1/3 the cost of a full frame one (all else equal), and probably as much as 1/5 the cost depending upon what technologies are in the image sensor. When you add in the 3x (rule of thumb) implied cost to consumers from parts cost to manufacturers, you get a huge differential in retail price between APS-C and full frame (again, all else equal). You can increase that differential by pulling out a few additional costs here and there, as well. Thus, a US$2500 APS-C camera might match up against a US$4000+ full frame camera fairly well in terms of specifications, though it will still have a one-stop disadvantage in terms of equivalence.