I've written extensively about why the lower-end of the camera market is causing issues for the camera companies. With word that the D3500 and D5600 have finally dropped off Nikon's production lineup (though still available for the time being), there's little doubt in my mind that the tri-opoly of Canon, Nikon, and Sony are all wondering about what they should do with their APS-C (crop sensor) cameras.

On the one hand, crop sensor cameras can be produced at lower prices and thus trigger volume that best utilizes those big manufacturing plants each of them has put in place over the years. On the other hand, those lower prices can quickly cut into gross profit margin in ways that are destructive if the market keeps collapsing in size.

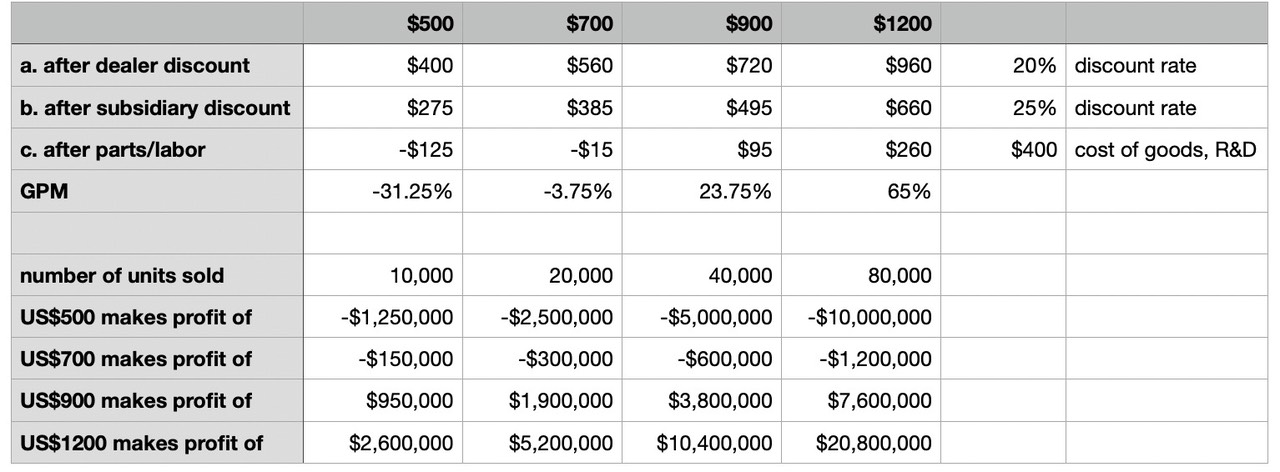

Let's make some assumptions and see how that maps out. I'm going to posit a camera that sits sort of in the middle range of APS-C pricing. Further, I'm going to say the all-in costs on producing such a camera are US$400. That includes cost of goods, R&D, manufacturing, and facility depreciation, among other things. Please note I'm pretending that this represents Nikon's fully burdened cost. It doesn't really matter how accurate that number is. I'm just putting a stake in the ground so that we can see what happens as volume and price change for such a product.

One word of caution: the camera makers build their charts from the company outward; I'm building from the customer backward because, well, you're a customer and you see things from that viewpoint The difference between these positions is that the camera companies will tend to base everything on GPM to establish what the price of a product is. I'm starting with the price we see at retail and working my way back to a calculated GPM using some of the numbers I know about how pass-along pricing of the distribution network works.

So here's a highly simplified spreadsheet to show what happens:

Typically, a products company wants gross margins in at least the 40% range, which happens to be somewhere between my two rightmost columns. If we price the product initially in the right-most price column (US$1200) and offer discounts over time that reduce it down to the third price column (US$900), then we're probably going to have a lifetime GPM that is in the range we want it to be.

To date, the camera companies have mostly centered on reducing cost of goods (which effects line c: in the chart). At some point, however, continuing to do so weakens the product by making it do less or be of lower quality, so you can't do that forever. It is a reason why mirrorless is preferred by the camera makers over DSLR: the same basic camera built as a mirrorless entry will cost less to make than the DSLR one; the mirrorless version has fewer parts—most of which benefit from economies of scale—and mirrorless has fewer manufacturing steps and alignments.

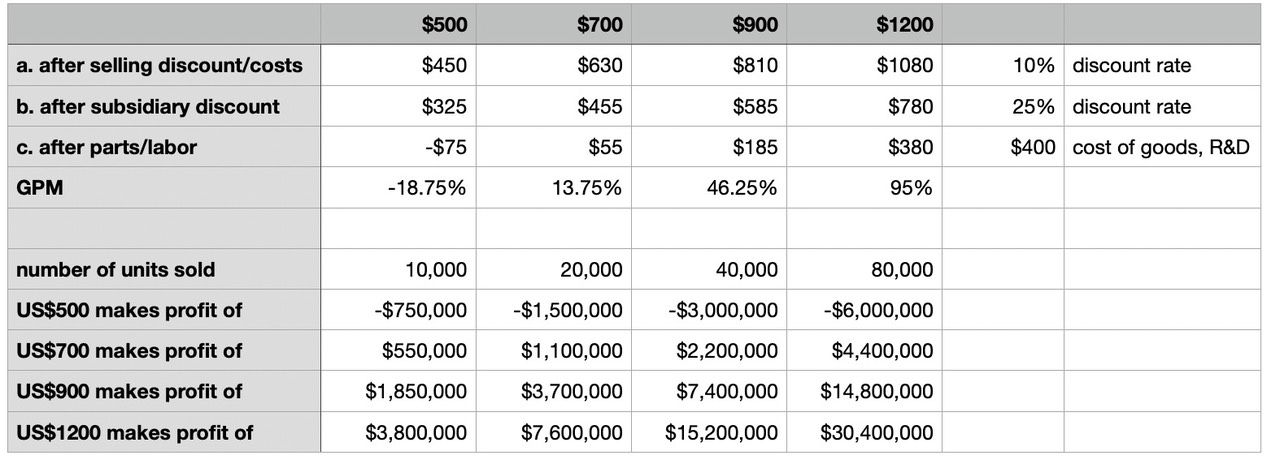

Which brings me to a point I've made before: the real problem for the camera makers in a declining market that is mostly mirrorless is in the a. and b. lines, particularly a.). 20% is actually probably slightly higher than the average discount the camera makers are giving on this sort of product to retailers and online vendors. But I'm using it anyway to illustrate my point: let's cut that discount rate in half:

In such a scenario, the camera maker can either (1) cut the product price to customer, thus likely increasing demand; (2) pocket more money; or (3) a combination of the two. We haven't made any change to product. We haven't changed the cost of operating subsidiaries (line b.). All we've done is something impacting how the product is sold to customers.

What would that be?

Simple: direct sales supported by more advertising and affiliate program fees. A typical affiliate program fee is 3%, not the 20% the camera makers have been offering the large dealers (note my change to the wording in line a.). That leaves us another 7% to deal with other costs and promotions associated with doing direct sales.

I've been asking this question for about a decade now: which camera maker is going to be first to completely back away from retailers and go all direct? For a long time we all thought that would be Pentax, but they're still mostly clinging to their old ways, but doing so with far fewer dealers and much smaller subsidiaries. We've seen a few lens makers use Kickstarter-type campaigns—essentially a direct outlet—to get new products off the ground. But we really haven't seen any of the major companies go all in.

OM Digital Solutions, the new company that inherited the Olympus Imaging group, may be the one that does it first. Indeed, if I were their advisor, direct would have been at the top of my list of things to do. The current m4/3 crowd is reasonably loyal, there are strong ambassadors/influencers available, the volume is going to go down in the transition almost no matter what OM Digital Solutions does, and they are going to want to get "closer to" each and every remaining m4/3 user while searching out some new ones.

Note that the camera makers mostly all have been concentrating on the "easy" part of the market. Full frame is sold at a much higher price than crop sensor, but with really only one part that costs significantly more (the image sensor). Thus, it's easier to preserve margins with full frame. Indeed, you may have noticed that other than Nikon—a curiosity since that isn't their usual position—the trend has been towards higher priced full frame products. Lower volume, higher margin is one way to keep the boat afloat, though over time the boat becomes smaller.

And so I return to my point: crop sensor is the place where the camera makers are all trying to figure out what their strategy should be. Yes, you can push more volume at US$500 than you can at US$2000, but that low-end market is the one in most decline in volume, so margins start to get problematic unless you've really nailed the product lineup. But you and I as customers couldn't correctly tell anyone what "nailing the product" means at US$900-1200 right now, and that's awful close to the full frame entry point, so there's confusion and head-scratching going on all over Tokyo as they ponder the same question.

It's not helping that we have supply chain issues, a pandemic that's altering spending/saving habits, retailers that may or may not be open to customers in some jurisdictions any given week, and even trade disputes/agreements that aren't fully resolved. Thus, when the camera makers look at their current numbers, they have to try to figure out why they are what they are. Is it a short-term disruption taking away volume that they would otherwise have, or is the problem they're seeing today permanent? They can't even accurately predict when the factors that are adding to their confusion will be resolved.

I don't quite know what to say (okay, I always have something to say ;~).

Cameras like the Canon M6 Mark II, Fujifilm X-S10, Nikon Z50, and Sony A6100 live in the "gray zone." They're all very good cameras. They're all I (or probably you) need for a lot of tasks, particularly travel photography. But do they have a future? Hard to say. But for now it's looking like the D3500 and D5600 don't have a future, and I suspect that Canon will decide the same for most of their Kiss/Rebel lineup, as well.

One word of caution to the camera makers: the expectations of customers for something that costs US$700 (e.g. D5600) is different than the expectations of customers for something that costs US$1300 (e.g. Z5). I've written it before, but this is another clear example of why I write it: as you charge more for something, you not only have to make it more desirable, but you also have to get closer to your customer and make sure you're fully serving their expectations and needs.

Put another way: we may be seeing the end of the consumer camera and the consumer customer. What would remain is the enthusiast and professional customers, and products for those groups. But enthusiasts don't stay enthusiasts if you don't give them what they want. Professionals move to another provider if you don't give them what they want. In other words, getting rid of consumer cameras won't actually "fix" the problems that the camera companies have, it just changes them to something they traditionally haven't been as good at doing. Eek.