News/Views

How’s the Bonding Going?

So, you received a new camera for the holidays. At this point you’ve likely had time to fiddle with it, but today’s headline question is the important one: have you bonded with your new camera yet?

I’ve been preaching some form of this notion since I first started writing about cameras. Your camera is a tool. You have to learn how to use that tool. The very best practitioners don’t just learn their tool, but the tool becomes second nature to them. They know exactly what it will and won’t do and how to coax it to do what they want.

At some point users become so close to their tools that you’d be very ill-advised to try to pry them from their hands and substitute something else.

To some degree this explains those hanging onto DSLRs. Mirrorless is indeed a different experience (tool) than DSLR, and once someone owns a near-perfect DSLR such as the Nikon D850, it’s tough to convince them to start the bonding process from scratch with something else. This is one of the reasons why sticking with a brand is useful during transitions: a Canon RF camera these days definitely has the traditional Canon EOS touch, feel, and more (the early R and RP models did not do that well, though, which explains Canon’s slow start to getting full frame traction in the mirrorless world). Nikon has moved their DSLR user experience mostly unchanged to the mirrorless Z System (though they continue to fiddle with small things that have me wondering why they’re moving my cheese).

Some of the recent “complaints” about the Sony A1 II intersect with today’s topic: the II model didn’t really change much, so why would I need to pay to upgrade to it? (That was also a common topic in the height of the DSLR era, as model iterations often didn’t change much.)

Bonding (usually) isn’t a natural thing: it takes study, time, and practice. You might resist that bonding at first because, well, your new toy tool is very different. However, if you don’t bond with it, I can pretty much guarantee that it either gets stuffed into a closet and rarely used, or you’ll be looking for a new camera soon.

How Does That Lens Look?

I’m not home as I write this so don’t have access to my full lens set or the ability to set scenes up to demonstrate the difference, so we’re going to do this with words. In some ways, working with words is better, because we won’t get hung up on things you do or don’t see in a compressed JPEG image on whatever size display you’re looking at.

A question that came up several times in my recent LA appearance had to do with “which lens is better?” That’s not an answerable question without more parameters being considered.

At one point I talked about the Nikkor f/1.8 S primes versus the Nikkor f/1.4, f/2, and f/2.8 primes. I believe these sets are all designed to very different standards. The words I tend to use for the f/1.8 S primes is that they are clinically clean. By this I mean that from center to corner they render with minimal aberrations that impact the capture. While the frame corner wide open may be softer than the center, it’s generally not by a lot, and it’s just a lack of acutance, not distortions caused by coma, spherical aberration, or field curvature. Linear distortions tend to be smallish and well corrected, too. Typically the biggest fault with those f/1.8 S primes tends to be something like vignetting, which is a natural attribute fairly predictable by image circle size, and tends to be easily correctable in processing. Thus the f/1.8 S lenses are clinical in their rendering.

The f/1.4 primes that Nikon recently introduced, along with the 26mm f/2.8, 28mm f/2.8, 40mm f/2, and even the 50mm f/2.8 macro Nikon has produced, are designed to a different standard. One that is more traditional, where accuracy of information in the corners isn’t considered as important. However, those blurry corners also are designed to be a bit like bokeh: soft and dreamy is better than stretched, messy, and busy. Nikon went through a period in the F-mount where they started paying much more attention to that, and we got several lenses—such as the 58mm f/1.4—that were sharp in the center wide open and “well behaved” otherwise. Back in the film era, a number of Nikons had clear color fringing in the corners, and that was something that called attention to itself, so we’d never call that well behaved.

Clinical versus Well behaved. Two different design approaches.

One of the longer discussions we had in Los Angeles—we were in proximity of the Hollywood sign, after all—was that filmmakers, and now videographers, tend to like lenses that aren’t clinical. That’s because they want you paying attention to the subject, and not get distracted by something else, especially things in the corners. Coupled with the inherent blur that comes with 24 fps, you want the things that aren’t your focused subject(s) to be blurred, too, particularly if the camera is moving or rotating (both detail and nasty artifacts in the corners coupled with motion call attention to themselves). Some video-specific lenses are notorious for not even attempting to be the sharpest tool in the box—that older actor doesn’t want any age wrinkles showing—but even if the center is what we’d all agree is sharp, the Hollywood gang really doesn’t want that to be true all the way out to the frame corners.

On the other hand, if you want to jar a movie audience, you do pick a lens that is brutally sharp, you narrow the shutter angle, pick up the frame rate, and voila, instant impact. I’ve noticed a lot of recent movies, particularly horror and blockbuster action ones, that will make a lens and settings swap for an action scene that puts you on edge and doesn't let your eyes relax anywhere in the frame, but then falls back to their regular lenses and settings for everything else.

One area where Nikon doesn't always get this right has to do with rendering of background lights out of focus. The 135mm f/1.8 S Plena does get this right: round, out of focus blur to the corners. Most of Nikon's other primes tend to have blur circles that get cut by things that shade the image circle, which results in cats eye in the corners. In watching a lot of streaming shows these days, I can almost tell which lenses are being used solely by what happens to something like a string of holiday or decorative lights in the background that are not in focus. If those aren't round all the way into the corners, it's likely a recent Nikon or Sony lens on the camera ;~). I wonder if RED dare tell Nikon that they need to fix this?

But getting back to the headline question, there's a very specific answer that tells you the difference between a really well-designed lens and one where shortcuts were taken: are you noticing things about the lens's look other than clinical versus well-behaved? In other words, are you even noticing a specific attribute of the lens, at all?

Generally speaking, if an attribute of a lens stands out on casual observation, that's not something you want in the "look" of your lens. Back in the film era, some of the lens look was masked by the layers and grains involved with film. Indeed, some companies tried to hide chromatic aberration by designing to a specific film stock (whose layers would dictate where red, blue, green were recorded). When we moved to DSLRs, those older lenses no longer looked as good as we thought they did because of that. Nikon, for example, started changing their lens design with the old 17-35mm f/2.8D, which came out with the D1 in 1999. The older 20-35mm f/2.8D, by comparison, shows lots of things you notice immediately: it's not clinical or well-behaved on a digital camera.

But let's get back to the point: do you want your images to look clinically correct wide open? Then the f/1.8 S lenses are your choice. On the other hand if you want your wide open images to look well-behaved, you can dip into the other optics Nikon is producing (e.g. the f/1.4 primes) without fear.

In the zoom lenses, the Tamron-produced set is (mostly) well-behaved, while the Nikkor f/2.8 S zooms are clinically sharp.

Your choice. Nikon is giving you that choice, and you should be happy they are.

Update: it seems like my use of the word "clinical" is bunching up a few folk's underwear. I'm going to stick by that word usage, as I believe it correctly captures my sense of what the S lenses are doing: they're like you'd expect in a proper clinic: clean, organized, nothing out of place, no random element that shouldn't be there. The word "clean" by itself does not fully capture the nature of the S lenses. Moreover, I'd argue that you can have "clean blur," in the sense that the blur is just blur, without unwanted elements added to it. I do not believe the word "clinical" is in any way pejorative; I think that bias I see in some people's interpretation of my words is coming from something else in their life that makes them think clinics are bad. Indeed, I suspect they're applying the third definition in The American Heritage Dictionary: objective and devoid of emotion, coolly analytical. As an analytical sort of dude, I find no problem with that ;~). Moreover, objective seems to be something an objective (optical element) should do.

Personally, I find my use of the words "well behaved" more of a problem and not fully capturing what I'm trying to say, the opposite of how most people are responding to the two ways of referring to lenses I used.

As a writer I spend long periods of time pondering word usage. In my twenties I used words poorly, as my copywriter ex-wife would gladly tell you. With each passing decade I've put more thought into them and tried to make sure what I was thinking was properly reflected in what you read. There are benefits to age, after all.

The real thing to take away from the article is that we have two very different design approaches by Nikon with their Z-mount lenses. Indeed, there may be three or four once we drill down and examine everything more carefully. The S side of the Z-mount offerings are some of best and most consistent rendering optics we've seen from anyone (though Sony GM is now pretty much there, too, other than linear distortion). The remaining lenses can be very good, but they have personality.

I haven't yet run the f/1.4 primes through their paces—I just picked them up from some crazy owner at some random camera store in Los Angeles over Thanksgiving—so I reserve the right to revise my opinion on those (though I didn't offer much of one other than a parenthetical phrase). One reason why a few reviews haven't yet appeared is that I'm spending a bit more time trying to fully evaluate certain aspects of lens design. As I started developing this Clinical versus Behaved hypothesis, I started diving deeper into certain kinds of testing to try understand what was driving that thought. That's proving trickier than I first thought, as I now am starting to understand that, at least in the Behaved lenses, it's the intersection of several design aspects that drives that, not one individual one.

Smartphones v. Cameras 2024 Edition

In the smartphone versus dedicated camera comparisons I keep seeing, there's an interesting sub-theme that everyone seems to be missing. It actually corresponds to why I decided to write Mastering Nikon JPEGs (due in Q1 2025).

Put simply, everyone is comparing smartphone "build-a-scene" with camera defaults.

What do I mean by this? Let's start with "build-a-scene." Almost all smartphones today run with the sensor actively before and after any "shutter release" action. They take anywhere from eight to 32 images and run the image processor on all of them to create the "moment" you pressed the shutter release, but with additional information from the sub-frames. This is how smartphones look less noisy than their sensors are: they're stacking static portions of the image to remove the photon randomness caused by how little light got to the image sensor.

The latest and greatest smartphones do even more machine-learned processing than that; it's one of the reasons why Apple started putting Neural processing cores in Apple Silicon: to speed that up. Edge detection, motion detection, and a host of other detections are all done on the full set of pixels before producing a final image. The so-called Portrait modes first subject detect, then process the subject and background frames differently.

Some people call this computational photography, though most of the algorithms I've seen are really just machine-learned post processing done in real time. In the end, both iPhone and Android devices are essentially doing one heck of a lot of pixel pinching, pushing, crunching, inventing, and more.

Could you do the same with say, a Pixel shift image stack in a dedicated camera? Absolutely.

Meanwhile, the dedicated cameras in pretty much all of the image comparisons I've seen are essentially "taken at camera defaults." The reasoning behind this goes way, way back (20 years or more). Essentially, it boils down to "I guess this is what the camera makers wanted us to see." Virtually every reviewer or comparison maker probably thinks they could create better out-of-camera images than the camera defaults, but they don't have the balls to try that in public.

What the camera makers have always had to do is make devices that move to the mean for an average user that doesn't want to spend any time thinking about setting things. Mostly because it starts to get too complicated to do anything else (remember, even the smartphones are using AI/machine learning to do it at all).

So what's really being compared is Auto Processing (smartphone) versus Auto Settings (cameras).

Frankly, I think the camera makers missed a beat or two along the way. That's particularly true of fixed lens cameras, but it's become true of mirrorless cameras, as well. If the image sensor is running all the time, as it is in those two cases, you'd think that you could build a better understanding of the scene that you can apply when the photographer actually presses the shutter release. Instead, it appears that almost all dedicated cameras look briefly at the most current information, make simple adjustments, then punt that data if anything changes (focus, setting, composition, you name it). The most recent single sample taken prior to the shutter release seems to be what generates white balance, exposure, and color decisions.

One thing I noticed once Apple started letting us iPhone users get to the original data (or at least a subset of it) was that I could get better-looking images out of my smartphone than all of Apple's intelligence could. Hmm. That corresponds to what happened when the camera makers gave us raw image formats ;~).

Unfortunately, most of the customers using a camera of any sort, perhaps nearly all of them (>90%), want automagic, a word I invented something like 40 years ago. In other words, press a button and the machine does all the thinking, setting, and rearranging for you. What is really being compared in every one of the smartphone versus dedicated camera comparisons I've see to date is "how's the automagic work?" I'll give the gold crown here to Apple first and foremost, with Google a step behind, and Samsung, et.al. right there at their tails. Dedicated cameras bring up the rear.

Funny thing is, Nikon at one time worked on this problem with Coolpix. With things like Best Shot Selection they were doing exactly what the smartphone makers jumped on later: don't just look at one frame! Nikon also deployed a version of Live Photo (something Apple also later added) as well as a bunch of other things. I can't say anything more here due to NDAs, but at one point I was hired as an expert to do patent search and analysis in exactly this area. It's interesting that the camera makers didn't defend a turf they had already started exploring.

Unfortunately, the camera makers are now in a tough situation. The R&D cost of full battle with the smartphone capabilities while running an image sensor constantly and improving that with neural engines doesn't spread well among the few remaining units the Japanese are selling of dedicated cameras these days. In actuality, even the phone makers are grappling with that same problem now that smartphone sales have stalled on a volume plateau far above the dedicated cameras. One reason why you're seeing Apple pour so much of each iPhone generation difference into the camera side is that it's still the one point where they can clearly differentiate and improve compared to other smartphones, but you have to wonder how long those legs are. Apple's marketing has already turned to AI as the new differentiator, for example.

So what's Thom's Maxim here?

Thom's Maxim #237: If you have all the data, you can always do better than a built-in automated process.

Yes, automatic features are nice to have. No, they don't produce the best possible results.

Global Shutter Fervor

Canon announced a new global shutter image sensor available to other companies this week, and that has all the photography Web sites salivating over possible APS-C global shutter cameras.

The problem? Canon's available sensor is a 16:9 crop, essentially Super35, not APS-C. It's also only 10.3mp, which would be considered low for modern still cameras (though it allows for full pixel use 4K video at 60P).

Yes, there are rumors that the eventual R7 Mark II will have a global shutter, but it doesn't seem that this new available-to-all chip is a precursor of that, particularly considering that the current R7 is 33mp.

Will there be third-party video cameras that use this chip? Unclear. The only client I know of using Canon's previous chips is Illunis, an industrial and security camera company.

Let's Charge for Cropping Guides

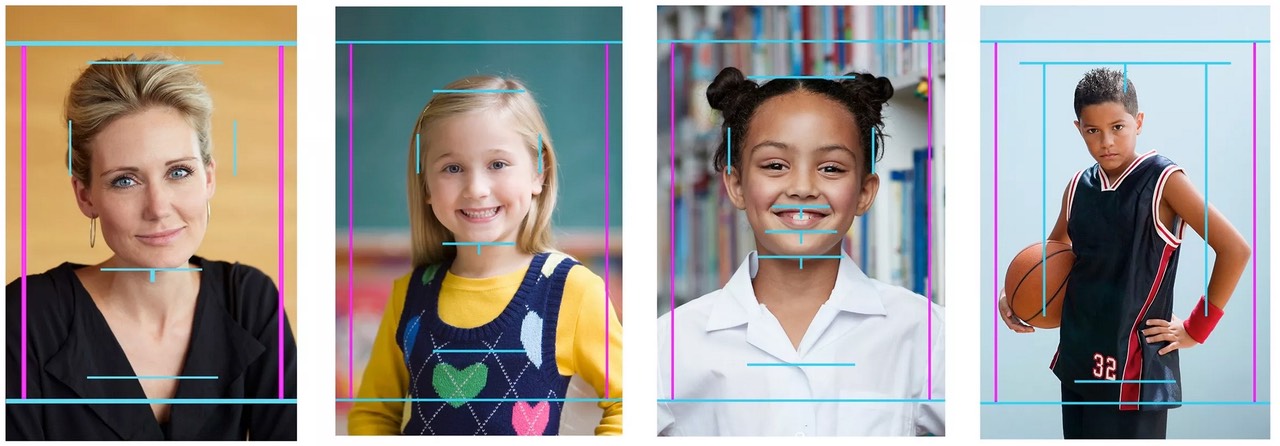

Sony was the first to announce that you could obtain custom frame lines in the viewfinder for a small wad of Benjamins, now it's Canon's turn, though slightly less custom.

R7, R10, and R50 users can pay US$120 to have a Canon Service Center add cropping guides to their cameras. As you can probably tell from the examples Canon shows (above), these are designed to provide you specific body/head positions for 8x10 portrait prints. You get four guides, each of which is selected with a new menu item after you send your camera into Canon for the "addition."

If you want all your portraits to look the same, I suppose this is useful. If you're doing enough portraits to justify needing such a guide, you could accomplish the same thing by simply using (near) fixed positions for the subject and camera and a marker on one of those cheap add-on LCD protectors for a lot less money. I also think it's ironic that Canon offers this with three lower cost APS-C bodies, but not the full frame ones, and that the guide cost is actually 15% of the lowest cost body you can do this with. 15% extra to add one convenience feature. Yikes.

Nikon users, are you next? Are you ready for an extra cost set of gridlines?